Today, Australia is ranked the second-largest gold producer behind China. In 2016/17 alone, Australia produced 284.5 tonnes or 9.15 million ounces of gold. While nowadays, miners today sit in air-conditioned vehicles operating large pieces of advanced machinery, during the gold rush of the 19th century, miners panned for gold in creeks and rivers or dug underground in highly dangerous conditions.

The results of the discovery of gold in Australia are well known. The massive increase in population transformed Australia, and Victoria in particular, from a small, largely rural community to a modern, thriving economy.

As geologist Richard Maddocks explains:

The gold rush of the 1850s to the 1880s propelled Melbourne from a small sleepy village to one of the world’s most affluent cities.

Many present sporting institutions all had their origins in the gold rush; the Melbourne Cup, Australian football, Test cricket all began during this period in Melbourne. Victoria led the world in progressive social reforms like the “8-hour day” and widespread voting rights (largely as a result of the Eureka Stockade and leading to universal suffrage in the 1890s). Melbourne’s architectural heritage from this period is evident as are cultural and educational institutions such as the National Gallery of Victoria, the Melbourne museum and the University of Melbourne. The collections and facilities of these institutions are all based on the prosperity directly caused by the gold rush.

On 26 February 2019, we will release the Welcome Stranger: 150 Years stamp issue, which commemorates the discovery of the Welcome Stranger nugget in 1869, near the town of Moliagul, Victoria – the largest alluvial gold nugget ever found, with a nett weight of 2,284 troy ounces (71 kilograms). The stamp features a photograph by William Parker showing Richard Oates, John Deason, Catherine Deason and others re-enacting the discovery of the nugget, as well as a replica of the nugget.

Alluvial gold is the gold mined from creeks and rivers. This makes up for a small amount of the gold that is mined today (most comes from the veins and lodes in hard rock). Most of the alluvial gold sources in Victoria were mined out in the 1850s and 60s.

Large nugget finds were relatively common in Victoria during the 19th century, with the Geological Survey of Victoria of 1912 listing more than 1,800 of them; Victoria is recognised as the world’s best location for large nuggets.

Having said that, Richard Maddocks says that the discovery of the Welcome Stranger nugget is particularly amazing, when we consider that gold is usually only found as very small particles.

“Most alluvial gold found in creeks is not more than fine dust with larger pieces rare,” says Richard.

Modern mines nowadays operate with gold concentrations less than three parts per million (equivalent to 3 grams per tonne of ore). In these mines seeing gold at all can be unusual. Most geologists at modern mines will have a few pieces of rock on their desks with a few specks of gold that they proudly show to visitors, so to consider a mass of nearly pure gold weighing 71 kilograms is truly amazing.

The real value is not in the monetary value but in the extreme natural rarity and beauty of such a find. Nuggets of the 19th century were all melted down ultimately to be minted into coins. Large nuggets found today tend to be bought by private collectors or institutions and are therefore preserved.

Richard Maddocks has 30 years’ experience working in gold mines in Western Australia, Papua New Guinea and South America. Richard provided expert assistance to the researcher on the Welcome Stranger: 150 Years stamp issue and has a personal interest in Australia’s Gold Rush.

“Most of my family came to Victoria in the 1850s looking for gold and ended up settling in gold mining towns like Bendigo, Maldon and Talbot.”

We asked Richard to explain how gold develops, why it’s valuable and how gold-discovery techniques have evolved.

As to the formation of gold, Richard explains:

“Gold is concentrated in the crust through geological processes over millions of years. Very high pressures and temperatures deep in the earth can mobilise gold into a solution with other minerals like quartz and this can then be concentrated into today’s economic deposits. Continental drift, subductions zones and magma deep in the earth can all play a part in forming gold deposits. Erosion and weathering can then expose these gold deposits with some gold being weathered into creek beds and rivers.”

Gold’s value comes from its use as money and as a store of value.

“Until the 1930s gold was used in coinage. Australia used to mint millions of gold sovereigns for circulation. When these coins were taken out of circulation during the Great Depression the government kept the gold as part of their monetary reserves. The Reserve Bank of Australia still has 3.79 billion dollars of gold in storage equivalent to about 80 tonnes. Currency traders also trade in gold as it is a defacto currency,” explains Richard.

As discussed above, Richard points out that the main difference today compared to the 19th century is mechanisation: advanced machinery versus a compressed air hammer, for example. Large open pit mines of the modern era, where rock can be broke up cheaply, also means that much lower-grade ore can be mined.

Mining in the 1850’s gold rush started from alluvial sources in creeks. Pans and cradles were used to separate the gold from sand and gravel. When the primary source of the alluvial gold was found, usually quartz veins with gold in them, these veins were dug out and then crushed to liberate the gold. To exploit these quartz veins on a larger scale requires expensive machinery to mine deep into the earth and to crush the ore containing the gold. This lead to the development of larger company mining with deep shafts and large stamp batteries producing thousands of ounces per year. Large companies still produce the vast majority of gold produced today.

A big difference is also in the attention to safety. Mining in the 19th century was characterised by a very high accident rate, resulting in many fatalities; mining, especially underground, was seen as a hazardous activity with rock falls and silicosis claiming many lives. Mining today is much safer with fatalities thankfully a very rare occurrence.

And as for the likelihood of another large nugget being found?

“Never say never!” says Richard.

“Large nuggets are still found today in Victoria and Western Australia. A large one like the Welcome Stranger is likely to be found where known nugget occurrences have been previously recorded, so the area in central Victoria around Moliagul, Wedderburn, Dunolly and Kingower are likely places. The buried deep leads of Ballarat also produced a lot of large nuggets, but access to these is difficult as modern infrastructure now covers these areas.”

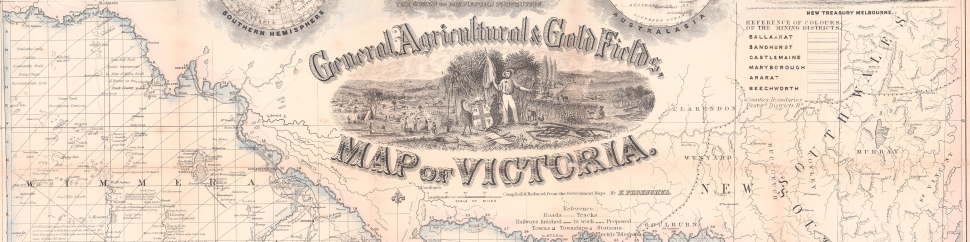

Banner image: F. Proeschel, Central Agricultural & Goldfields map of Victoria, Melbourne, 1860, National Library of Australia MAP RM 970

The Welcome Stranger: 150 Years stamp issue is available from 26 February 2019, online, at participating Post Offices and via mail order on 1800 331 794, while stocks last.

View the gallery and technical details from this issue

This article was produced at the time of publication and will not be updated.

You might also like