Australia is home to many spectacular and highly significant caves. Caves are not only fascinating natural subterranean environments, with interesting formations, but they may also be important cultural sites, or home to rare fauna and ancient fossil deposits that provide us with valuable insights into evolution and ecology.

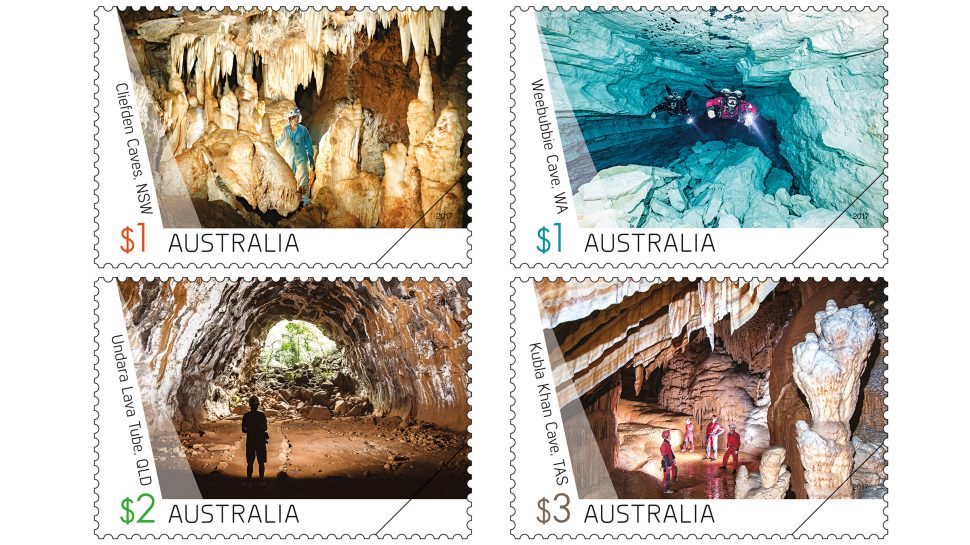

On 2 May 2017, Australia Post released its Caves stamp issue, featuring four incredible and varied caves and cave systems from around Australia: Cliefden Caves, in New South Wales, Weebubbie Cave, in Western Australia, Undara Lava Tube, in Queensland, and Kubla Khan Cave, in Tasmania. Each of these important and fragile environments is restricted in terms of public access (Undara is by guided tour and the other three caves are permit-only), so this stamp issue provides an exciting window into a hidden underground world.

To learn more about caves, we spoke with Stefan Eberhard. Stefan is a scientist with a PhD in ecology. He specialises in subterranean ecology and organisms, including their relationship to each other and their environment such as caves and groundwater. Stefan provides research, assessment and consulting services to government departments, cave management and tourism associations and the resources industry. In other words, Stefan knows a lot about caves and is passionate about their significance and value.

“When I was a youngster, my parents took me and my siblings to a Kelly Hill tourist caves on Kangaroo Island in South Australia. I remember feeling curious and excited at the beauty of the formations, and the sense of mystery – there were dark corners and tunnels, which the guide said ‘down there, the cave goes on for another mile’. I found the mystery fascinating and exciting, and that curiosity and urge to explore caves has stayed with me. Discovering new cave passages, and species new to science, still excites me, and the mystery and beauty of caves continues to motivate me.”

We talked to Stefan about caves and karst generally, as well as the specific caves featured in the stamp issue.

“A cave is natural hollow in a rock beneath the surface of the earth, not an artificial cavity such as a mine shaft. Whether it’s the ocean eroding a sea cave, a stream dissolving a limestone cave, or lava flowing down to form a lava tube, they are all different types of caves."

"The term karst denotes a landscape with distinctive land forms arising from water-soluble rock. Karst is best developed in carbonate rocks, such as limestone, dolomite or gypsum. These rocks are soluble and easily dissolved by rainwater, sea water, streams and groundwater. This process of weathering dominated by solution produces distinctive landforms such as caves, sink holes, and springs, and most drainage occurs underground in karst. The essence of karst is the whole landscape, not just the caves. Caves are a characteristic land form of karsts, but not all karsts have caves as we know them (subterranean spaces that are large enough for humans to enter),” says Stefan.

“Because caves are very stable environments that are long lasting and protected from normal surface weathering processes, they can contain living organisms, fossils and mineral formations that have remained relatively undisturbed for thousands and even millions of years. For example, in Jewel Cave near Margaret River there are the bones of thylacines (Tasmanian Tigers) that accidentally fell into the cave and became lost before they perished thousands of years ago, and their footprints are still clearly visible in the soft mud of the cave floor, and the prints look fresh as if they had been made yesterday,” says Stefan.

“In this example, and many other respects, caves are highly fragile environments that can be irreversibly damaged by human actions – from a careless footprint to deliberate vandalism or inappropriate development. While cave tourism development and cave exploration do have environmental impacts, they are not the biggest threats. I think tourist caves are a good thing because they foster appreciation and understanding of the values of caves and karst. Tourist caves are a valuable economic and educational asset in many ways, so long as they are developed and managed in an environmentally sensitive manner."

"More significantly, it’s more often changes to the landscape and environmental processes above the ground that may pose a bigger threat to caves and karst overall. Potential threating processes include deforestation, land clearing, agricultural practices, pumping and contamination of groundwater, sedimentation, mining, urbanisation and damming. With a lot of these external threats, you don’t see the impact immediately. The threats may originate kilometres away in the water catchment and may take decades, centuries or millennia to gradually impact the caves and karst. Many Australian caves and karst have been impacted to some degree in the past, however Australia is now a world leader in the conservation and good management of our precious cave and karst heritage,” says Stefan.

Cliefden Caves, New South Wales

Located along the Belubula River, the Cliefden karst environment includes one of the most significant cave systems on private land in New South Wales. The Cliefden Caves Landscape Conservation Area is listed on the National Trust Register.

“The caves at Cliefden are very well decorated and are of national significance. The Cliefden Caves Limestone Group is also an internationally significant site for Ordovician fossils. It was ranked among the 70 most significant fossil sites by the Australian Heritage Council in 2012,” says Stefan.

There are approximately 100 individual caves at Cliefden, which contain diverse speleothems, including rare pale blue formations. The blue formations are thought to be due to copper, chrome and nickel leaching through the limestone. Cliefden is also the site of the first discovery of limestone on mainland Australia in 1815, by surveyor George Evans. The stamp photograph, taken by Alan Pryke, features the beautiful golden stalactites and stalagmites of the highly decorated Clown Room in Cliefden Main Cave.

Weebubbie Cave, Western Australia

“The Nullarbor is one of the largest continuous karst areas anywhere in the world, with many unique caves. Some of these caves contain very significant fossils of mega-fauna,” says Stefan.

“The caves of the Nullarbor also contain a rich variety of cave-adapted invertebrates, such as blind centipedes, spiders and cockroaches. These caves are also culturally significant to Indigenous peoples. Caves were historically a very important feature in the flat and dry limestone plain, and provided a place for shelter and art, as well as a source of water and stone for making tools. The Nullarbor karst has World Heritage values on numerous criteria,” says Stefan.

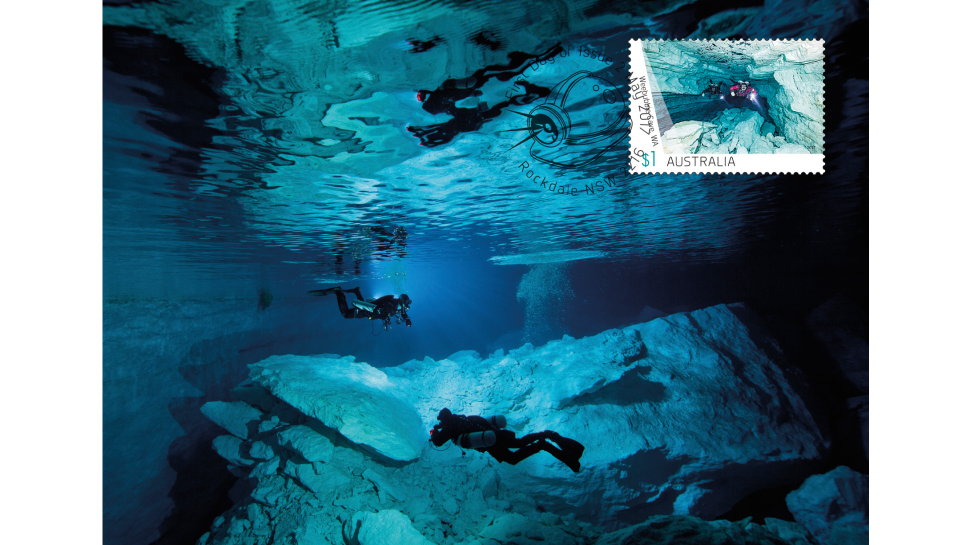

The Nullarbor is especially renowned for its underwater caves. One such cave is Weebubbie Cave, near Eucla in Western Australia – the deepest cave in the Nullarbor. Formed millions of years ago, it is a culturally significant site to the Mirning people. The stamp photograph, taken by Steve Trewavas, showcases the cave’s incredibly clear lakes.

“I’ve done a number of cave dives at Weebubbie,” says Stefan. “Put simply, it’s one of the world’s great underwater caves. It’s such an immense size, with outstanding grandeur and beauty. The clarity of the water is truly exceptional, and the rock is pure white, the visibility underwater is virtually unlimited. Diving through Weebubbie feels like flying through liquid inner space,” says Stefan.

Undara Lava Tube, Queensland

Undara Volcanic National Park is traditional country of the Ewamian people and is situated around 300 kilometres south-west of Cairns, Queensland. Undara is home to one of the longest lava tube cave systems in the world (“Undara” means “long way”) and the longest in Australia. Access to Undara Lava Tube is by guided tour only.

For millions of years Undara was an active shield volcano. Then, about 190,000 years ago, a single flow of molten lava poured down a dry riverbed. The outer layer cooled into a hard crust, while the centre drained away to leave a hollow tube in its wake. Surviving segments of the tube form caves and arches, including Mikoshi Cave which is pictured on the stamp, in a photograph taken by Alan Pryke, and Stephenson Tube, as pictured on the maxicard, above. Within these more than 50 caves, cool and moist pockets provide home and shelter to many animal species, including wallabies, bats, owls and cave adapted invertebrates including insects, spiders and centipedes.

“Undara is a highly significant site both in terms of its geology and ecology. The lava caves are rich in invertebrate species and it is the location of important research contributing broader understanding of adaptation and evolution in caves,” says Stefan.

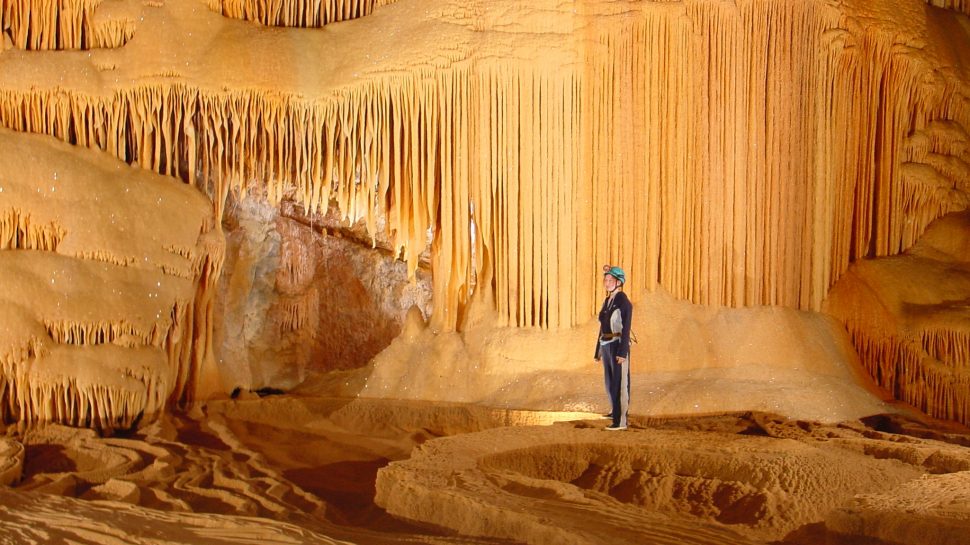

Kubla Khan Cave, Tasmania

Tasmania's caves are some of Australia’s most spectacular and significant. In the north of Tasmania, there are some incredible horizontal limestone cave systems. One of the most impressive is Kubla Khan, which is part of the Mole Creek Karst National Park, east of Cradle Mountain.

“Kubla Khan is the best decorated cave in Australia – nothing comes close to it in terms of sheer size, magnificence and beauty,” says Stefan. “The sheer profusion of formations is absolutely extraordinary and world class. It’s an internationally significant cave. The immense size of the passages, chambers and formations is breath taking,” says Stefan.

Kubla Khan Cave and its formations are named after the Samuel Taylor Coleridge poem of the same name. More than two kilometres in length, Kubla Khan’s incredible formations include the spectacular Silk Shop shawl formations, one of which is visible on the stamp. Another incredible feature is a towering 18-metre stalagmite known as the Khan, situated in the dome-shaped Xanadu chamber. A massive chamber called the Pleasure Dome is filled with rimstone pools and huge expanses of glistening flowstone.

The Kubla Khan stamp photograph was taken by Liz Rogers of Liz Rogers Photography. We interviewed Liz about the special requirements of taking photos in the deep, dark depths.

What was your path into both photography and cave exploration?

“I had a head start on caves compared to most people, as both my parents are cave divers. My dad was involved in significant exploration of the Australian Nullarbor caves in the early 80s and they both still cave dive. My dad was also a photographer and his advice, both when I got my first film camera as a pre-teen and then when I started taking cave photographs, was much appreciated.”

What do you enjoy most about both of these pursuits?

“I love the controlled nature of the cave environment and the way the only thing in the cave is yourself, your group and the things you bring with you. It's a rare chance to see unexplored parts of nature that have never been visited by another person. From a photographic perspective, the absence of natural light and the chance to shoot from unusual angles provides an almost studio-like setup, full of creative possibilities.”

Cave photography isn’t for the faint-hearted. Does it take a particular personality type to deal with the depths and the potential dangers?

“Cave photography requires some additional thought, both before entering the cave and while shooting. In particular it's important to have the right level of concern about damaging and dirtying camera gear. If I was too worried about the equipment, I'd never take it caving. But being too relaxed can be a recipe for a camera full of mud, and I wouldn't get the shot that way either.”

What do you need to consider when visiting these caves and photographing them?

“Caves are an isolated, ancient ecosystem. Any human impact made when visiting a cave could last forever. Formations that took hundreds of thousands of years to form can be destroyed with a single careless movement. When I'm caving with a camera in my hands I'm always conscious of my immediate surroundings, making sure to follow the Australian Speleological Federation’s (ASF) Code of Ethics for minimum impact caving. This includes staying on existing tracks rather than creating new ones, and making sure everything that you take into the cave comes out again.

When entering a completely dark environment to take photographs, the most important thing is to light it up. This means not just the flash on the camera but placing off-camera flashes in the cave. I use radio triggers in the dry caves and light sensors underwater to trigger the off-camera flashes to fire at the same time.”

What special equipment do you need for cave photography?

“The most critical piece of equipment is the pelican case and underwater housing, to ensure the camera is protected as we travel underground and underwater.”

You took the photograph featured on the Kubla Khan Cave stamp. What do you find most amazing about that cave in particular?

“Kubla is a stunning cave. It's unusual to see so many different types of formations in one place. I particularly like the huge hanging shawls and the stacked pillars. The opportunity to play with light and shadow and bring out the best in the formations was amazing.”

What is your favourite cave to photograph and why?

“So hard to choose! For decorations, Kubla Khan and Junee Caves in Tasmania. For huge tunnels, white walls and very blue water, Weebubbie is a great example of the Nullarbor Caves in WA. And you can't go past the big open sinkholes in Mount Gambier for some stunning sunlight-through-water shots.”

How did you feel about your photograph being selected for a postage stamp?

“I sometimes feel like caving and cave diving is such a small niche for photography that it gets very little attention from the outside world. The chance to show off the amazing underground world to a wider audience is fantastic. Everybody should get to experience a trip underground at some point in their lives, and maybe a glimpse will tempt people into trying it out.”

To learn more about Stefan Eberhard’s work, visit his website Subterranean Ecology.

To learn more about Liz Roger’s work, visit her website Liz Rogers Photography.

Banner image, courtesy of Alan Pryke

The Caves stamp issue is available from 2 May 2017, online, at participating Post Offices and via mail order on 1800 331 794, while stocks last.

View the gallery of stamps and technical details for this issue.

This article was produced at the time of publication and will not be updated.