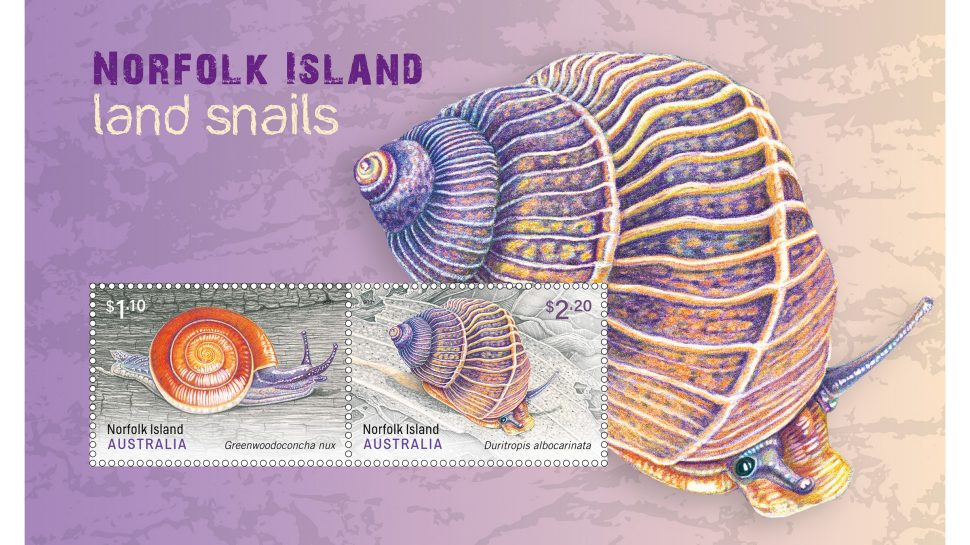

On 22 June 2021, we’ll release a stamp issue, illustrated by award-winning wildlife artist Janet Matthews, which showcases two tiny species of Norfolk Island land snail: Greenwoodoconcha nux, with its dark red-brown, flat spiral shell of around seven centimetres, and Duritropis albocarinata, which has wavy ribs and swirls on its purplish-brown conical shell of around six centimetres.

One of the experts who was well placed to answer questions from the philatelic researcher who worked on this issue was Dr Isabel Hyman, Scientific Officer at the Australian Museum, who not only knows a lot about snails but also about the approximately 60 described species of land snail described as endemic to Norfolk Island. Isabel completed a Bachelor of Science (Advanced), with Honours, at the University of Sydney. Her PhD project was a taxonomic revision of Australian helicarionids (a family of air-breathing land snails) and included a chapter on the helicarionid snail fauna of Lord Howe Island and Norfolk Island.

Isabel’s current role centres around a taxonomic revision of the land snails of Lord Howe Island and Norfolk Island, both hotspots of land snail diversity with high numbers of endemic species, despite the small size of these islands and despite the damage to species numbers from predation and habitat degradation and loss. The aim of the project is to have detailed data that allows investigations into the origins of these often-hidden fauna and to help mitigate against further extinctions. That means documenting and describing every species, describing new species where necessary, and investigating the relationships between them. This involves anything from collecting fresh material to document current distribution, describing and measuring shells and live animals, sequencing DNA, analysing data, and finally, publishing the results.

“My interest in molluscs first started when I was in my second year at university. I was offered the opportunity to do a research project with a scientist from the Australian Museum. I chose Dr Winston Ponder, Principal Research Scientist in Malacology. I was inspired by Winston’s obvious passion for his work, and a fascinating and detailed world was opened up to me. By the end of that project, I was hooked!” says Isabel.

“Snails make great study subjects for many reasons. There are still many species undescribed or very poorly known in Australia (and worldwide), so there is plenty still to be done,” adds Isabel.

There’s also an important conservation component to Isabel’s work. Land snails are very sensitive to habitat disturbance, and given their usually narrow ranges, they are extremely vulnerable to extinction.

“People probably don’t know that land snails are the group worldwide with the highest number of recorded extinctions. They are very vulnerable to habitat disturbance and to the introduction of predators. Also, when people complain about snails eating their garden plants, they generally don’t know that in most cases, the only snails you see in Australian gardens are introduced species. Native snails tend to be found in only quite undisturbed habitats. So, feel free to feed the common garden snails to your blue-tongued lizard!” says Isabel.

Islands tend to have high levels of endemic biodiversity. The number of endemic species on an island depends on factors like the island’s size, its habitat complexity and its distance from the mainland. Norfolk Island is close enough to other land masses for land snails to have colonised it on multiple occasions but isolated enough for these founding members to have diversified into a number of new species. The high number of species on Norfolk Island (around 50 surviving species) is particularly impressive when you consider the relatively small size (around 35 square kilometres) and young age of the island (formed only 2.3 to 3 million years ago).

“The number of species on Norfolk Island is difficult to judge at the moment – I hope I can give you a more precise answer in a year’s time, when we have finished our revision!” says Isabel.

“There were 70 species originally described, but we believe that this was a slight over-estimation and that the true number of unique species is around 60. I would estimate that around 8-10 of these are extinct – but even this number is not certain. Some of the island’s endemic species are tiny and extremely rare, making them very difficult to find,” adds Isabel.

Scientists have not yet given up on the species thought to be extinct. A team from the Australian Museum, including Isabel, travelled to Norfolk Island twice in 2020, to survey the island’s land snails, for the first time in 20 years. On each visit, a live population of a species feared to be extinct was located, including a population of Advena campbelli – a species that is currently listed as Extinct on the IUCN Red List and as Critically Endangered by the Australian Government. This species had been rediscovered by Mark Scott, a Norfolk Island resident, shortly before the Australian Museum’s visit.

“We hope this trend might continue! We still have several more trips planned, and each trip we will search the last known location of these species, as well as other regions where they are likely to be found,” says Isabel.

The main causes of extinctions or declines in Norfolk Island land snails are through habitat clearing and through introduced predators such as rats and chickens. Much of the island’s original habitat has been cleared, leaving native subtropical rainforest remaining primarily in the National Park (although pockets of native vegetation exist in some other locations as well, including some reserves). While the staff of the National Park and the Norfolk Island Regional Council carry out an extensive pest control program, keeping rodent and chicken numbers down and giving the native species the best chance of survival, predation is still having a significant effect on some land snail species. Interestingly, the most vulnerable species to rodent predation are the largest ones, since the rats tend to preferentially prey on them.

“In March 2020, we discovered that the two remaining large snail species on the island were both reduced to single, very localised populations, making them highly vulnerable to any adverse conditions, such as unusually dry weather, an increase in predation, or any changes to their habitat. One species was so reduced in numbers that we found just a single specimen alive on our first trip and only three specimens on our second trip,” says Isabel.

Results like these led to the development of an off-site breeding program, in conjunction with Taronga Zoo, Parks Australia, and the Norfolk Island Regional Council. This important project has recently commenced, with a founding population of each species collected from the island and transferred to Taronga Zoo.

“The long-term plan is to move the populations back to Norfolk Island, in rodent-proof enclosures. If this proves to be successful, it could be extended to other vulnerable species on the island as well. This may be the only chance to save species that have been reduced to such low numbers but are still under significant predation pressure,” says Isabel.

Isabel is not only excited about the captive breeding project but also about Norfolk Island snails featuring on stamps: “I have always enjoyed collecting stamps, and when the subject matter is Norfolk Island snails, two of my favourite things are combined into one! It’s also wonderful to celebrate our often unseen and overlooked native invertebrates – and to showcase how beautiful as well as how vulnerable they can be.”

The Norfolk Island: Land Snails stamp issue is available from 22 June 2021, online, at participating Post Offices and via mail order on 1800 331 794, while stocks last.

This content was produced at the time of the stamp issue release date and will not be updated.

Banner image: Adnan Moussalli, Museums Victoria.