“Through language, people preserve their community’s history, customs and traditions, memory, unique modes of thinking, meaning and expression.”

International Year of Indigenous Languages website: iyil2019.org

The United Nations (UN) has declared 2019 the Year of Indigenous Languages (IYIL 2019). According to the UN, there are approximately 370 million Indigenous people around the world. Language is a crucial way for these people to express history and culture and to participate in all aspects of society, yet the UN also reports that 40 per cent of the almost 7,000 languages spoken around the world are in danger of disappearing. This loss of language can be seen in the Australian context. An estimated 120 Australian Indigenous languages are still in existence, yet 90 per cent of these are considered critically endangered, so there is a real risk that these languages will disappear within our lifetime.

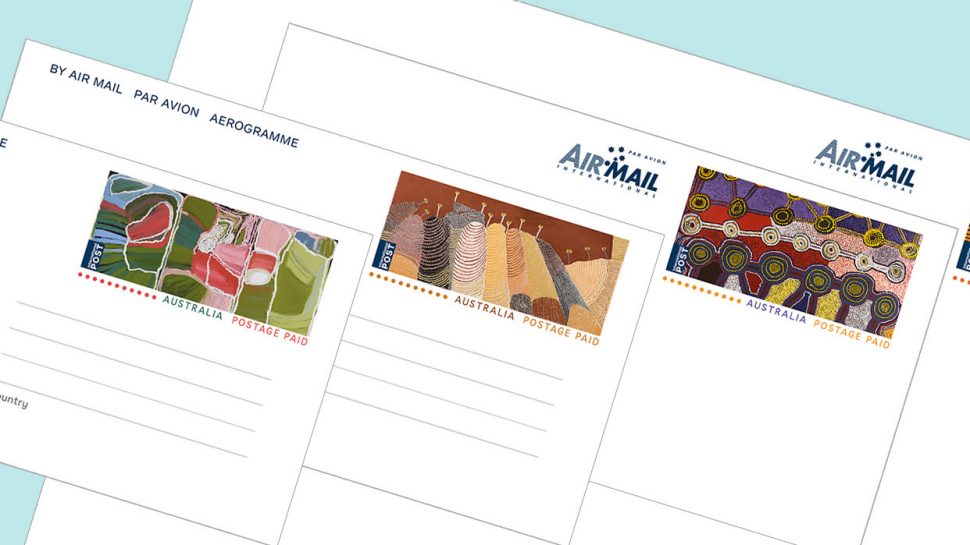

The International Year of Indigenous Languages stamp issue, released on 30 April 2019, seeks to both commemorate IYIL 2019 and highlight the significant work being done in Australia to preserve and promote Indigenous languages. This work covers a range of language types and contexts, including languages acquired by the youngest generation as first language; languages with a few elderly speakers and a desire by younger people to learn them; and languages revived from historical sources and Elders’ memories.

These efforts are supported by community-led language programs delivered by more than 20 Indigenous language centres across Australia – funded by the Commonwealth Department of Communications and the Arts’ Indigenous Languages and Arts program. The program provides funding to community-based organisations for projects that support participation in and maintenance of Indigenous culture through languages and arts, including supporting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples' capacity to teach, preserve and revive their own languages. The many and varied projects being undertaken as part of IYIL 2019 are being highlighted on the Department’s website throughout the year.

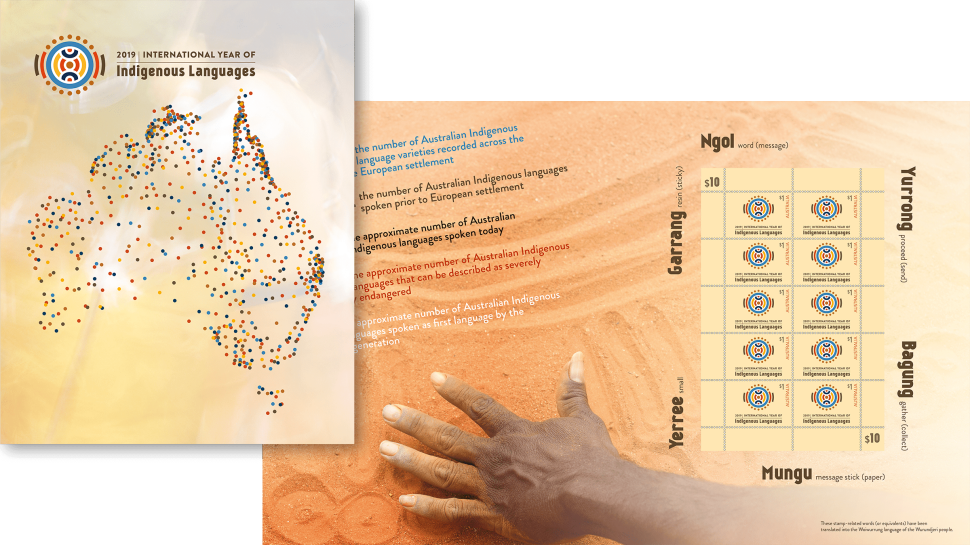

The sheetlet pack released as part of this stamp issue includes some stamp-themed words translated into the Wiowurrung language of the Wurundjeri people – the head office of Australia Post is situated on Wurundjeri traditional lands. The cover of the sheetlet pack features a map of Australia comprised of dots – these dots represent the centre point of regions associated with the hundreds of Indigenous language variations, both current and historical, recorded in AUSTLANG, the Australian Indigenous languages database developed and maintained by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS).

We conducted a Q&A with the Chief Executive Officer of AIATSIS, Craig Ritchie, to learn more about the work of AIATSIS and the importance of language.

- What is your background and your role at AIATSIS?

Barayn marrung, dhanggu nyuwayi Craig Ritchie – Good day, my name is Craig Ritchie.

I am a Dhanggati and Biripi man who is the Chief Executive Officer at AIATSIS. I’m also proud to be representing Australia and AIATSIS as co-chair of the UNESCO International Year of Indigenous Languages steering committee. I grew up in rural NSW and only recently begun engaging with my own Dhanggati language at age 51.

- What is the mission of AIATSIS?

The mission of AIATSIS is four-fold: to tell the story of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australia; create opportunities for people to encounter, engage with and be transformed by that story; support and facilitate Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural resurgence; and shape our national narrative.

- Why is IYIL 2019 an important initiative?

IYIL 2019 is an important initiative that provides an opportunity to highlight the value of Indigenous languages in Australia and around the world. It raises awareness of the need to support maintenance and resurgence of Indigenous languages. This contributes to positive outcomes to the health and wellbeing of Indigenous Australians related to cultural transmission and identity; and Informs non-Indigenous peoples around the world about the countries or regions they live in.

As I said in Paris recently at the IYIL 2019 launch, “Language is more than just a means of communication. It is a repository for history, wisdom, identity and culture. Indigenous languages contain unique systems of knowledge that are valuable to our modern challenges. They are also fundamental to the world’s cultural diversity and social integration. The good health of Indigenous languages is in everyone’s best interest.”

- What do you hope is achieved in Australia as a result of IYIL 2019?

This year presents a great opportunity to have a national discussion about the role Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures play in shaping the nation and better informing our identity. More than 250 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages were spoken on the continent at the time of European settlement in 1788, today only 13 of these languages are acquired as first language by the youngest generation – this is a crucial element for language maintenance.

IYIL 2019 places focus on reversing this alarming statistic in Australia. The good news is that for the many languages with just some elderly speakers, documentation and programs to transmit that knowledge to younger generations; and programs to revive languages from Elders’ memories and historical sources have never been stronger, but all contexts require understanding and support from the wider community to ensure revival and ongoing use of this cultural heritage.

Nyiyanang wuunggalu! – Let’s work together!

- What are some of the key initiatives being undertaken by AIATSIS during IYIL 2019?

A full list of events and detailed information will be added to our IYIL webpage throughout the year. However, AIATSIS also has ongoing and specific programs to highlight Indigenous Australian languages in IYIL 2019.

AUSTLANG is a database containing 850 records of documented language varieties (languages, regional dialects, clan-based dialects) from referenced sources and about 300 records of “languages” which are in the historical record, but not confirmed. AUSTLANG supports discovery of written and recorded materials about and in language. AUSTLANG language codes are currently being implemented in the National Library of Australia and Trove, which leads the way for libraries across Australia and the world to follow AIATSIS’ leadership in this regard.

The AIATSIS Dictionaries project provides funding for final productions stages of twenty dictionaries of Indigenous Australian languages. This includes dictionaries from all language contexts – languages still spoken such as Warlpiri (Central Australia), languages spoken by some Elders but not younger people such as Gija (north-east Western Australia), and languages revived from Elders’ memories and historical sources such as Dhurga (south-east New South Wales)

In partnership with the Department of Communications and the Arts and Australian National University, AIATSIS is working on a National Indigenous Languages Report to be released later this year. This follows our National Indigenous Languages Surveys we did in 2014 and 2005 and will provide the most updated, comprehensive account of Indigenous Australian languages.

The AIATSIS Australian Indigenous Languages Collection was established early in 1981 to bring together printed material written in Australian Indigenous languages. It now contains more than 4,500 titles and has been described as highly significant, leading to its inclusion in the UNESCO Australian Memory of the World Register.

The AIATSIS Languages Collection also includes a significant range and depth of unpublished manuscripts, audio and moving image items, many of which were compiled and recorded by early AIATSIS (AIAS) research grants. The AIATSIS Languages Collection supports language maintenance and revival by collecting and sharing resources collected since 1964.

- From a linguistics point of view, what are some of the key ways that Indigenous languages differ to English?

Indigenous languages that cover most of the Australian continent are closer in structure to Latin than English in that they add suffixes to nouns to indicate their role, rather than using word order for this as English does — as a result, they have very free word order. All Indigenous languages have grammatical categories such as tense, aspect and mood on the verbs along with rich sets of pronouns and suffixes on nouns, adjectives and adverbs. An example of this from Pintupi (Northern Territory) is:

Watingku marlu wakarnu

“The man speared the red kangaroo”

Wati = ‘man’

-ngku = suffix that marks the agent

Marlu = ‘red kangaroo’

Waka- = ‘to spear’

-rnu = past tense suffix

In my Dhanggati language you have to choose between two ways of saying “we” ngati for two people and nyiyanang for more than two people, whereas English lacks the dual set of pronouns.

- How have Indigenous languages been handed down among generations? And what methods are used in modern times?

Language acquisition is how we all learn our “mother tongue” and this ensures continuity of a language. In Australia acquisition by the youngest generation is restricted to about 13 languages in remote communities, English and other Indigenous languages are second language.

In places where this has ceased, there are two main streams of “handing down”. One is learning from the few Elders who still speak the language through various programs and the other is to reconstruct the language from historical sources, and teach language formally in classrooms and informally in context.

All languages require documentation, i.e. a description of the grammar and a dictionary. Language Centres and linguists work closely to develop such references, so that learning and teaching resources can follow.

- There appears to be an increased effort to document Indigenous languages and produce dictionaries. What are some of the difficulties inherent in projects like this, and what kind of progress is being made?

Language documentation has been practiced since the first grammar of an Indigenous Australian language was compiled in 1834, using Ancient Greek and Latin as frameworks! Modern linguistic methods refine this approach and the general public would be amazed to learn what is known about language structure, and the wonderful grammatical complexity of Indigenous languages.

All languages need dictionaries as a reference and to preserve language forms, even if they die out of everyday use. It’s no different from English. Dictionaries take years to compile; AIATSIS is proud to support the last stages of production for 20 projects to get them through to publication.

Readers of this blog can visit AUSTLANG to explore what is known about Indigenous Australian languages; it leads to our Languages Collection for further reading.

- Aside from verbal language, some of the other ways that Indigenous communities have traditionally communicated include sand drawing, song and dance. Can you elaborate on this?

All world languages incorporate non-verbal communication; in art and other cultural expression. Sign language is common across Indigenous language groups in Australia and is similarly complex to spoken forms. Sign languages are used in regional and urban communities, but you have to be quick to see people using them, they are often quite discreet in those contexts. Elsewhere sign language is more visible, and is used in hunting, and contexts where spoken language is inappropriate.

The International Year of Indigenous Languages 2019 stamp issue is available online, at participating Post Offices and via mail order on 1800 331 794, while stocks last.

View the gallery and technical details from this issue

This content was produced at the time of the stamp issue release date and will not be updated.