While shipwrecks are a relative rare occurrence these days, since the 1600s more than 8,000 shipwrecks have been recorded as occurring in Australian waters. Of these, however, only around 2,000 have been located.

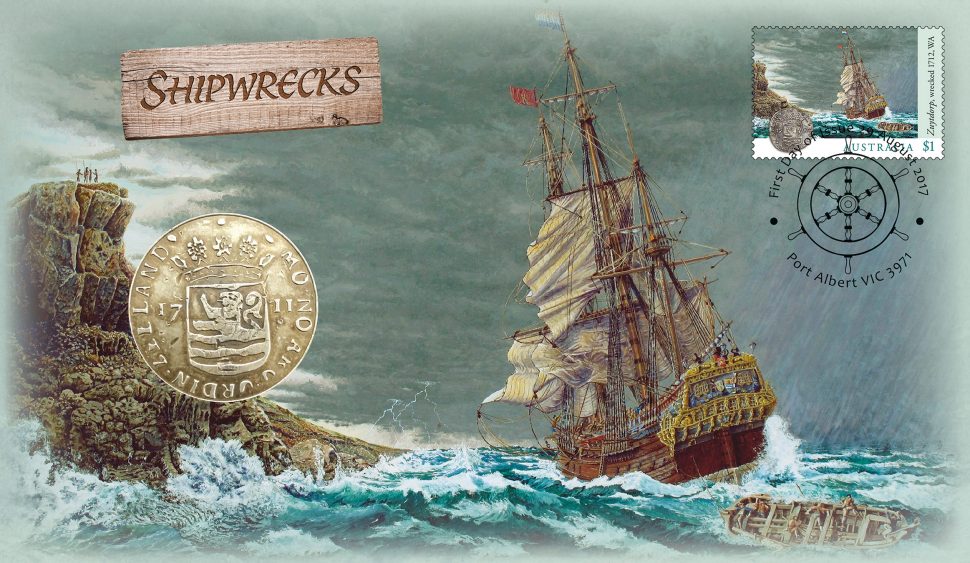

The Shipwrecks stamp issue, which will be released on 29 August 2017, presents three historically and archaeologically significant shipwrecks. The stamps feature paintings by maritime artists of each wreck event, together with a recovered relic, to show the context of each voyage.

Australia protects shipwrecks under the Historic Shipwrecks Act 1976 (Cth), including automatic protection for all shipwrecks more than 75 years old. More than 6,500 wrecks in Commonwealth waters are protected under the Act, and there is complementary legislation in each state and the Northern Territory. The Act also currently protects half a million historic shipwreck relics and artefacts in various public and private collections.

For this three-part article series, we spoke with some of the curators who assisted researcher Jane Levin with the stamp issue, to learn more about each wreck and the incredible work they do in caring for and preserving them. We also spoke to one of the artists whose detailed research helped to beautifully capture a moment in history.

The Zuytdorp

In June 1712, with an estimated 200 or more passengers and crew on board, the VOC ship Zuytdorp was wrecked on the Western Australian coast. Captained by Marinus Wijsvliet, and heading from the Netherlands to Batavia (now Jakarta, Indonesia), it crashed onto rocks at the bottom of cliffs just south of Shark Bay, now known as Zuytdorp Cliffs. Even today, the currents and cliffs of this area are notoriously treacherous.

As well as conveying various trade goods, the three-masted 700 ton ship was carrying a highly valuable load of silver coins, valued at around 250,000 Dutch guilders. Wreck artefacts were discovered near the site in 1927, including silver coins dated 1711. These coins helped archaeologists in the 1950s and 60s to identify the wreck as that of Zuytdorp. There is an area of the wreckage site called the “carpet of silver”, because of the number of coins that still remain embedded there. One of these coins is featured on the stamp, and a medallion based on the coin design is featured in a limited edition medallion cover.

When Dutch-born artist Adriaan De Jong conceived of painting the wrecking of the Zuytdorp, which appears on the stamp, he had much to consider, especially as no survivors of the wreck came forward to report the event or give their version of it. He also had to think about the weather and other circumstances that may have led to the wrecking event, let alone what the ship itself may have looked like, including the detailed sterns typical to VOC ships of the era.

“If one paints a seascape the weather condition plays an important role in picturing the scene,” says Adriaan.

“This shipwrecking most probably took place in the beginning of June 1712,” says Adriaan. “To the antipodes of the northern hemisphere, this is the beginning of the winter season. The weather is more changeable and it is not uncommon that changes announce themselves with fronts of rain and thunder that drift from the sea towards the land. In the southern latitude of 27º 11΄, where the Zuytdorp perished, it is possible that a fast upcoming front with thunderstorms caught out the sailors on board the Zuytdorp while sailing on a northern course not far from the coast,” he adds.

“Knowing that the ship moved in northerly direction towards Batavia, it is noteworthy the wreck came to rest sideways against a coast stretching south-southeast to north-northwest, but with the stern pointing northward! A track gouged out under water where the keel rammed the ground at first indicates the ship was driven headlong onto the underwater rock shelf. Stuck by the bow, a south westerly wind with accompanying wave condition would then have pivoted the ship around until the stern pointed to the north and driven it further on shore where it also sank,” says Adriaan.

In Adriaan De Jong’s evocative painting, he shows how the Zuytdorp has already turned sideways in front of the rocks with her stern pointing to the north, which Adriaan describes as “speculative but plausible”.

“A maritime expert explained to me that the vessel must have been driven hard up against that cliff and that possibly the crew managed to bring out ropes from the masts to the cliff and careen the ship with its masts against the cliff, thus enabling a large number of people to abandon ship. During excavations half of the broken ship’s bell has been found wedged in the side of the cliff, indicating how close the vessel must have been to this cliff. In recent times there has been much speculation about what may have happened to the Zuytdorp survivors and the main conjecture is that they may have integrated in the local Aboriginal communities. That was also my reason to place the Aboriginal figures on top of the cliff,” says Adriaan.

Adriaan also carried out extensive research into the potential distance between the Zuytdorp and the ship immediately behind it, the Kockenge, to determine the likelihood of the Zuytdorp experiencing different weather conditions to the reportedly ‘fine’ weather conditions experienced by the Kockenge around the same time. Adriaan examined VOC charters from the time and then used physics to calculate the likely speed each ship was capable of. Adriaan concluded that the Kockenge would have reached the same location a good seven to 10 days later, which could explain differing weather conditions experienced by each.

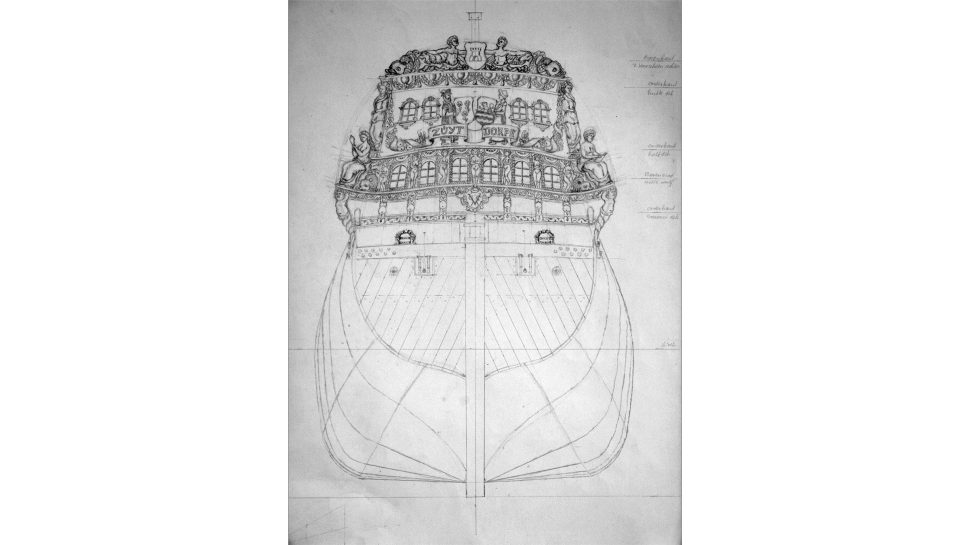

Meticulous research was also undertaken to determine the size and appearance of the ship itself.

“The VOC charters of the time are very detailed,” says Adriaan. “For instance, a ship is imagined to be divided in nine cross-sections and for each section six points, port and starboard, are given what the width and height of each point is. It is thus possible to reconstruct the lines of these ships. The charters are for ships of 160, 145 and 130 feet and there can be no doubt that the Zuytdorp was built in accordance with the charter for 160 foot ships. Having the lines plan of the Zuytdorp it is then possible to rotate this into a position which would suit my idea of how to paint the vessel,” he adds.

“What is more problematic is determining the detail. We do know that the name of a VOC ship was almost always depicted in an emblem on the ornate stern. For details of the ornamentation I have relied to a large extent on art works by the marine artist Ludolph Backhuysen, who painted around the time of the Zuytdorp. One of his engravings, for example, includes a ship which has a carving of a woman holding a mirror in her hand (representing Prudence – a careful lady who can look ahead but, thanks to the mirror, can also see what’s happening behind). In addition, the emblem representing the name of the ship must have had a direct connection with the village called Zuytdorp in the province of Zeeland in the Netherlands. It so happens that this village has a coat of arms which is a yellow field on which three blue flowers grow. This coat of arms is left from the middle of the stern. I have also included a second coat of arms which is that of the province of Zeeland,” explains Adriaan.

To learn more about the Zuytdorp, visit the Western Australian Museum website.

In our next instalment, we look at the incredible tale of the HMS Pandora, which sank on the Great Barrier Reef, after returning home from her mission to capture the notorious Bounty mutineers.

The Shipwrecks stamp issue is available from 29 August 2017, online, at participating Post Offices and via mail order on 1800 331 794, while stocks last.

This article was produced at the time of publication and will not be updated.