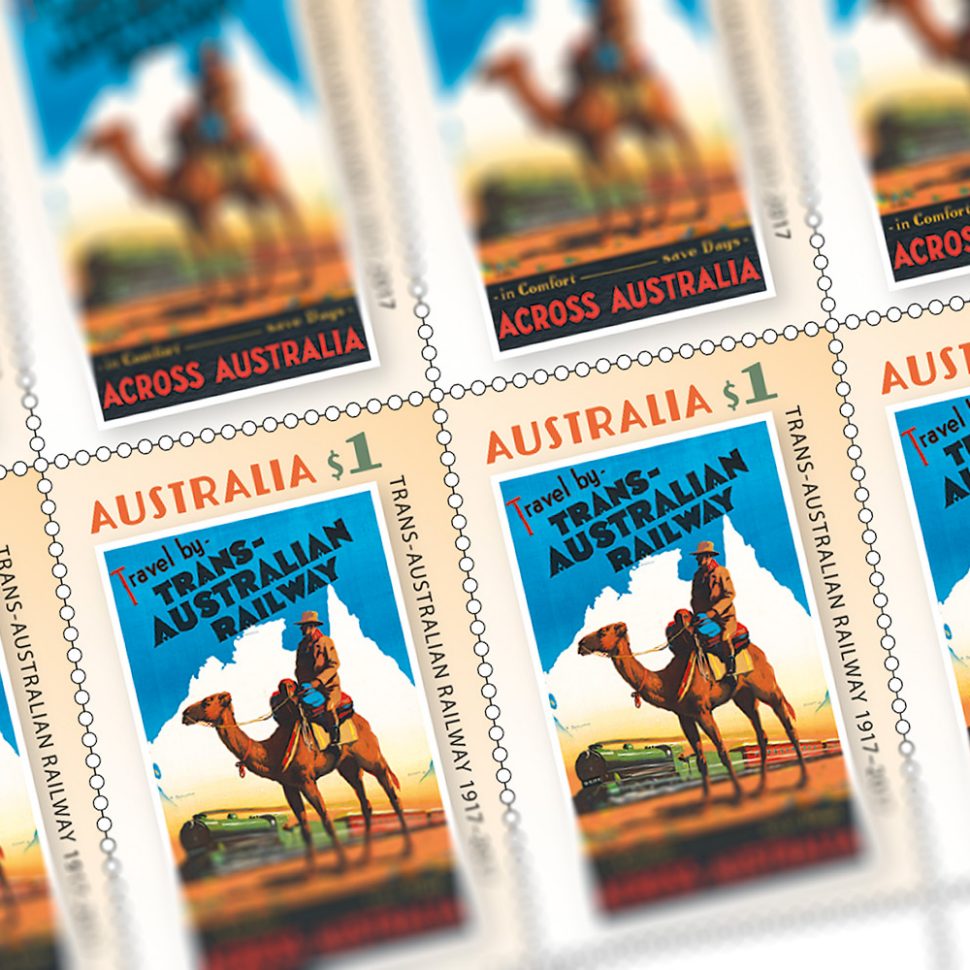

In this new series we take a look at Australian stamps through the ages, starting with a history of Colonial (State) stamps of the nineteenth century.

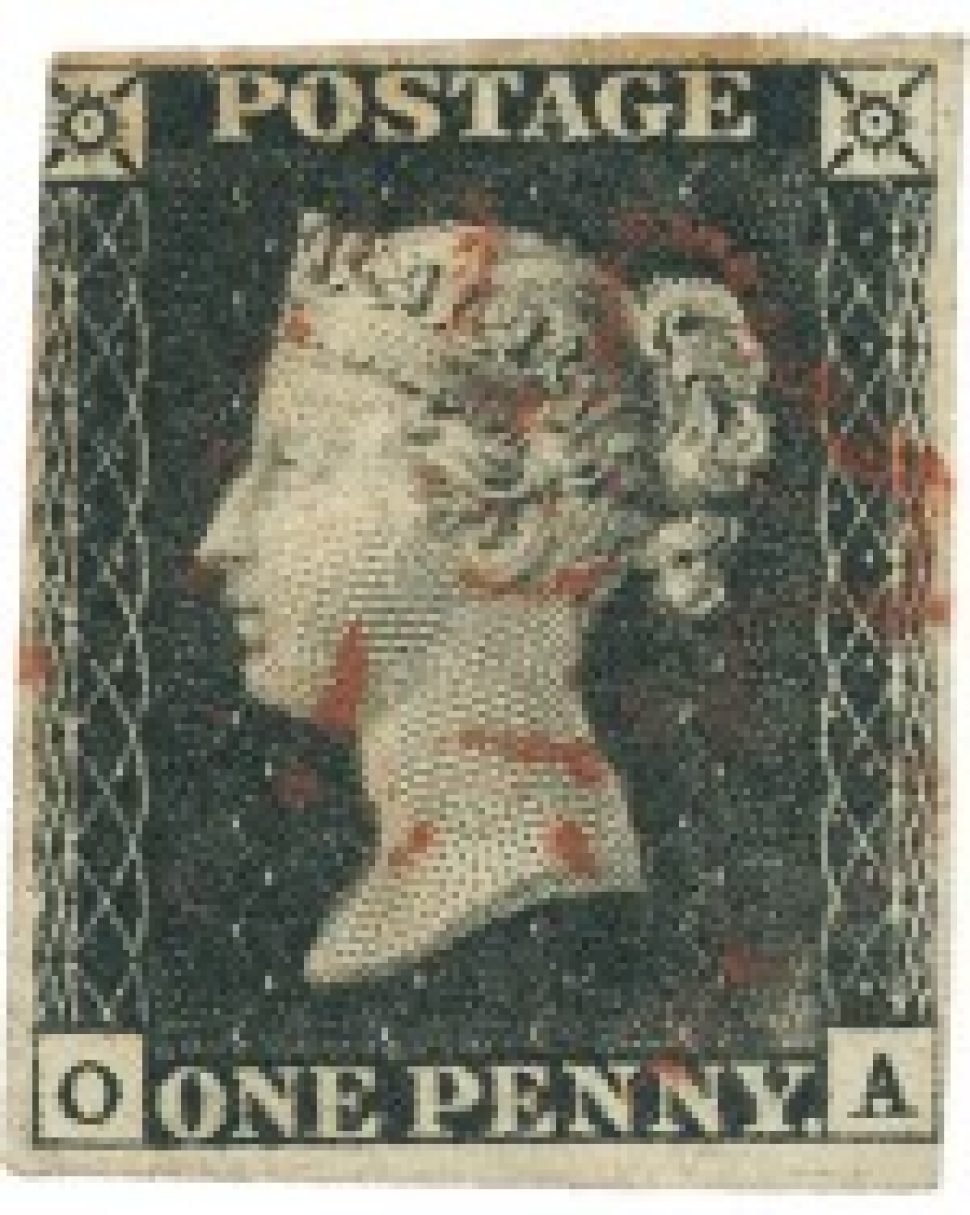

Pre-paid postage stamps originated in the United Kingdom in 1840, when the world’s first stamp – the “Penny Black” – was issued. The Australian colonies were early experimenters with prepaid postage using stamps.

Nineteenth century Australian stamps are characteristically ordinary in appearance. They were not intended to appeal to collecting instincts, nor were the designs changed regularly to avoid public boredom.

Stamps served to prepay postage and any elaborate elements in their designs was to thwart potential forgeries.

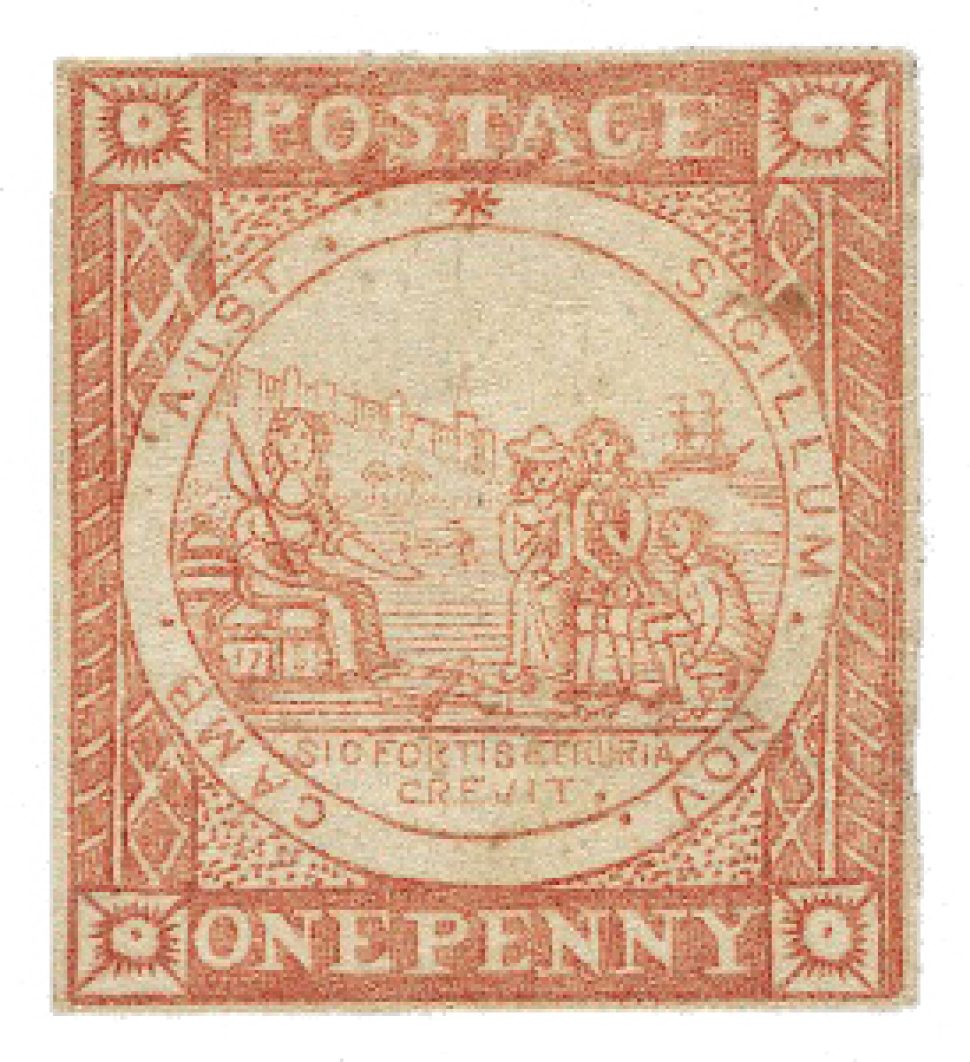

New South Wales issued the first stamps in Australia on 1 January 1850, introducing prepayment of postage with simplified charges for mail:

- 1d for delivery within town limits

- 2d delivery elsewhere within the country

- 3d for carriage by ship

These New South Wales stamps were called the “Sydney Views” by collectors because the design featured the colony’s seal of 1792, which depicted an allegorical female (industry) directing the attention of newly arrived convicts to the virtues of honest work in the form of oxen ploughing.

The other Australian colonies followed the lead of New South Wales and adopted prepayment of postage by issuing stamps – Victoria (then known as Port Phillip District) on 3 January 1850, Tasmania (then known as Van Diemen’s Land) in 1853, Western Australia in 1854, South Australia in 1855 and finally Queensland in 1860. Thus by 1860, Australia had six colonial postal systems, each issuing its own stamps, a practice that continued until after Federation.

Generally colonial stamps featured a profile portrait of Queen Victoria, a tradition beginning with the “Penny Black”. It's interesting to note the majority of stamp portraits of the Queen depict her as a young women at the outset of her reign: by the end of a 64-year reign the Queen’s profile remained unchanged on most Australian stamps.

There were variations in the royal portrait. Victoria’s first stamps, issued on 3 January 1850 and called the “Half Lengths” featured a half-length portrait of the Queen. Western Australia was distinctive, producing stamps in the pre-Federation era that featured the Black Swan as the chief motif rather than the Queen’s head.

In 1875, Victoria updated the royal portrait on its 1d stamp, a common usage denomination. New South Wales also adopted a contemporary portrait on 2d and 2 ½ d stamps issued in 1897. However, both colonies continued to feature youthful portraits on other stamp values.

In 1888-89 New South Wales made a significant departure from tradition when the colony issued a new stamp series, ranging in denomination from 1d to one pound (£1) to mark the centenary of European settlement. The “100 Years” series, as it was inscribed, was the first time in the world a government postal administration issued commemorative stamps. Unlike modern commemorative stamps, the 100 Years series were not issued for a limited period of sale, but remained on sale as an ongoing or “definitive” series. Some values in the 100 Years series were still current in 1913 when state stamps were replaced by a uniform Commonwealth series.

Another break with stamp design tradition involved Tasmania’s 1899-1900 six large-size stamps featuring scenic views. The pictorial series was intended to promote tourism in Tasmania, illustrating how governments had become aware of the promotional opportunities offered by stamps.

The importance of stamps as a promotional medium was most clearly demonstrated by New South Wales and Victoria in 1897 when both colonies issued charity stamps to celebrate Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. The charity stamps were sold at 12 times more than their postal value, with the difference being handed over to hospital charities. The experiment was repeated by Victoria and Queensland in 1900 for soldiers wounded in the Boer War, but it was much less successful and there were no further issues of charity stamps in Australia until 2011.

Australian colonial stamps were printed in England or locally. In some instances, local stamp production was a temporary measure until English-printed stamps were supplied. New South Wales and Tasmania contracted private printers to produce their first stamp issues. The printing plates were engraved by hand with each stamp image on the plate differing somewhat in detail. Queensland, South Australia and Western Australia had their first stamps printed in London by Perkins, Bacon Ltd., who also printed stamps for Great Britain.

New South Wales and Tasmania eventually replaced locally-printed stamps with Perkins Bacon issues. In the eyes of the colonial authorities Perkins Bacon stamps offered greater protection against forgery than the more crude locally-produced stamps. Usually, the colonies ordered an initial supply of stamps to be shipped from London, along with the printing plates and a supply of blank watermarked paper, so that further stamp supplies could be printed locally. The “tyranny of distance” made it impracticable to rely on the English printers to supply stamps on an ongoing basis.

After 1860, De La Rue replaced Perkins Bacon as the principal stamp printer for Great Britain and the British colonies. De La Rue were specialists in letterpress stamp printing, which differed to Perkins Bacon’s intaglio (or recess) process in that the stamp image was raised above the surface of the printing plate, giving stamps a characteristically flat appearance. Since letterpress printing was significantly cheaper than intaglio, the Australian colonies began printing the bulk of their stamps using plates made by De La Rue.

Victoria was distinctive with its stamp printing arrangements in that with the exception of two stamp issues, Victorian stamps were wholly produced in the colony (i.e. the engraving of the master die, the manufacture of the plates and the stamp printing were carried out in Melbourne).

Until around 1860, stamps were issued imperforate and scissors were used to separate stamps from the sheet. After 1860 the use of perforation in stamp production became standard. As a security requirement, stamp paper incorporated a watermark device. This was originally a numeral corresponding to the stamp’s denomination; for example “1” for 1d, “2” for 2d. At a later stage, an outline of a crown together with the colony’s initials formed the watermark. Shortly after Federation, the design of a Crown and A (for Australia) was adopted.

Colonial stamps, normally printed in one colour, were occasionally produced in two-colour if it was necessary to make certain stamps look more distinctive, such as high-denomination stamps versus low value stamps. In the mid-1850s, Victoria issued two-colour stamps for Registered mail and for Late Fee mail.

For many collectors it is the errors and varieties involved in stamp printing that are the most desirable items. Australian nineteenth century stamps are often thought too complex and lacking in appeal to be an interesting field to collect. Nevertheless, the great stamp rarities belong to the early colonial era. The majority of stamps of the 1850s and 1860s are valuable, particularly if they are unused (i.e. not postmarked). This is mainly because unused stamps were rarely purchased in the 1850s and 1860s for collecting reasons. Those stamps purchased for postage, which for whatever reasons did not get used on mail, are today’s stamp rarities.

The most valuable Australian stamp is from this era – the “Inverted Frame” 4d blue Western Australian issue of 1854. As a result of a transfer error in laying down the stamp image on a lithographic printing stone, the framework of lettering of one stamp image was inverted in relation to the Black Swan. This led to printing of one Inverted Frame stamp in each sheet, with only about 14 examples surviving today. Several Inverted Frame stamps are institutional collections, including three examples owned by Australian museums. Since Inverted Frame stamps have fetched around $80,000 – $100,000 at public auction many years ago, and would probably reach a great deal more if sold today. The stamp error is Australia’s most valuable object for its size and weight.

This article was produced at the time of publication and will not be updated.