The naming of Christmas Island seems to be a fairly straight-forward story: Captain William Mynors sailed past it in 1643, in the early hours of Christmas day, and named the island “Christmas Island”. However, when we look closer at maps from before and after this naming event, we can see both the shortfalls of navigation during the 16th and 17th centuries and the importance of accurate placenames.

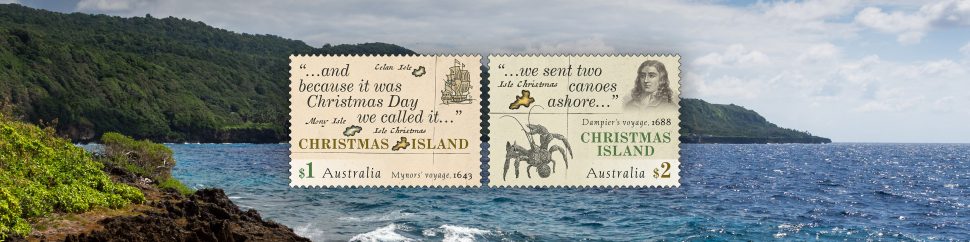

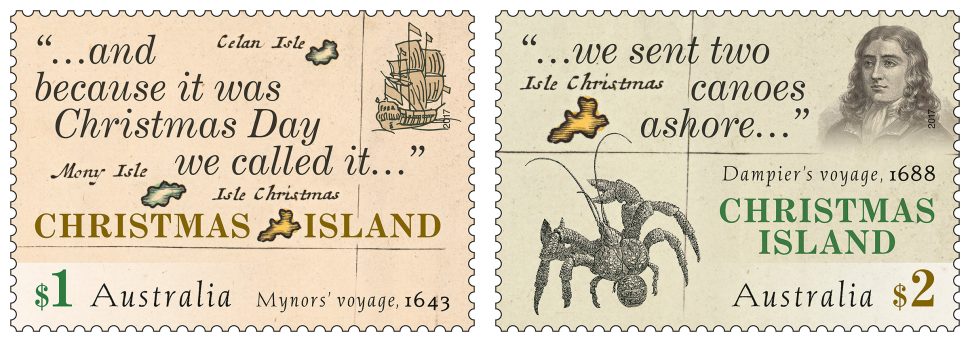

On 15 August 2017, Australia Post will release the Christmas Island: Early Voyages stamp issue, designed by Sonia Young of the Australia Post Design Studio. The stamps depict two important journeys in the history of the island.The first was by Captain William Mynors, as described above, and the second was by the Cygnet, with explorer and navigator William Dampier on board, whose crew made the first recorded landing on the shore in 1688.

The stamp design features an early map of the region by Dutch cartographer Joachim Ottens. Part of the conundrum in researching this map, and the many other early maps of the region, is understanding why there is often more than one island pictured where there should be one, why those islands were often given varying names (even after the naming of Christmas Island), and what those names could have possibly meant.

Of invaluable assistance to the researcher in solving this issue was Dr Jan Tent, an expert in linguistics and placenames. Jan completed an Arts degree (with Honours) in the 1970s. He majored in linguistics, as well as completing a Dip. Ed., and a PhD in Fiji English. Jan had a long-running academic career in linguistics until his recent retirement in 2014.

Jan first became interested in placenames during his Honours year in Linguistics, in 1976 and then renewed his interest while conducting some research in Fiji:

“I was conducting some research into early Dutch loanwords in Polynesian languages with Paul Geraghty, a colleague. I was born in the Netherlands and had part of my secondary education there, and therefore I am fluent in Dutch. This helped, of course, with my research, which entailed closely reading the journals of the early Dutch explorers of the 17th and 18th centuries. I started noticing interesting things about their place-naming. When I came back to Australia, the people of the Australian National Placenames Survey asked me to write some pieces on Dutch placenames in Australia. So it all went from there. I ended up developing a unit in placenames at Macquarie University, which I taught for four years until I retired. We are currently re-developing that unit for an Open Universities Australia unit,” says Jan.

During his research, Jan began reading all about Willem de Vlamingh and his encounter with Christmas Island. This led Jan to start collecting early maps of the region. It was in those maps that Jan started to notice the following interesting points: Many early maps contained more than one island in the area of Christmas Island, where there is only one. Christmas Island was either unnamed or named with either “Monij/Moni” or “Selam” (or variations thereof). Sometimes both names appeared. Even after the naming of Christmas Island, in 1643, the conundrum continued, with many maps including “Christmas I” or similar, but still not dropping the other names or the multiple islands until the 19th century.

“I naturally wanted to find out what “Monij/Moni” and “Selam” referred to,” says Jan.

What’s in a name?

“Toponymists (people who study placenames) try to discover who named a place, when it was named, why it was named thus, and what the meaning of the name is. Usually, we can’t find answers to all or any of these questions,” adds Jan.

In the case of Christmas Island, as discussed above, we know who named it, we know when it was named, and we know why it was named thus, and its meaning. However, the same cannot be said for the names that preceded (and, for a time, existed alongside) “Christmas Island”, such as “Moni” and “Selam”.

Jan’s extensive research into the topic resulted a journal article, published in 2016, in Terrae Incognitae (Vol. 48, No. 2: 1-23). In the article, Jan explores the topic in great detail, including studying 76 maps, dating from circa 1540 to 1904.

Possible meanings of the early names for Christmas Island

Monij

Jan believes that there are a number of languages that can be considered candidates for the origin of this name. This is because the maps all show languages from Javanese, Dutch, Portuguese or Sanskrit origin.

Some likely candidates identified by Jan include the Sanskrit word muni (sage, holy man, monk, silent) and the Portuguese word múni (a pious or wise Indian man). The Sanskrit word holds particular appeal, argues Jan, because of the parallel between “silent” and the remoteness of Christmas Island.

Selam

Jan believes that this possibly came from the Arabic word selam (peace, greeting). It is also an element in many other words, including the Hebrew greeting shalom. However, the most promising candidate is a Javanese (and Malay) word sela (from Sanskrit śilā ‘a rock, a stone’) meaning ‘precious stone’, given the ubiquitous rocky steep-to coastline of Christmas Island.

The reason for multiple names

“It’s not unusual for geographic features to be named several times by different explorers/navigators and be given different names. Navigators from different nations often did not have the luxury of having each other’s charts. These were keep strictly secret by the different maritime nations. So, along the coastlines of Australia, you get the Dutch coming along naming things, and then the English and then the French. They each had their own names. In the end, the vast majority of Dutch and French names were replaced by English names because Australia became a British colony. When you name a place, it is a metaphorical way of taking possession of the place. There are numerous Dutch names that no longer appear on maps (at least not modern maps). Most of these were replaced (either knowingly or unknowingly) by English names. Some Dutch names were simply calqued (i.e. literally translated), e.g. Steep Point (Western Australia) from Dutch Steijle Houck, South Cape from Dutch Zuydt Caep/Kaap, Red Bluff from Dutch Roode Hoeck,” says Jan.

“In relation to the Christmas Island context, I just think that Monij, Selam and Christmas Island were all names for the same island. It’s just that navigation during the 16th and 17th centuries was not at all accurate. The calculation of longitude posed huge problems because of the inability to keep accurate and reliable time aboard ships until the development of reliable and accurate chronometers. Because of this it was thought there were two or three islands in that neighbourhood when in fact there was only one. I don’t think the ‘ghost island’ theory holds much water. It’s just the same island named and charted on separate occasions. When navigation became much more accurate, cartographers and navigators realised there was only one island there. During the latter part of the 18th century, Christmas Island became the preferred name, mainly because the British took possession of it,” says Jan.

The importance of placenames

The Christmas Island example proves the importance of typonomy (the study of placenames), but so do contemporary examples.

“It is important to have placenames standardised in spelling and grammar and to ensure that there is no duplicate naming. The study of placenames is also important to historians, genealogists, cartographers, geographers and the like. Part of the problem we are seeing in the South China Sea centres around the names the various players in the conflict give the islands/reefs in question. Even the name “South China Sea” is contentious!” says Jan.

“There are so many interesting chapters in the exploration of Australia and the concomitant naming of places. On every map we can find a wealth of historical, cultural and linguistic information frozen in the names that people have given to places,” he adds.

“Placenames also form an integral part of a nation’s cultural and linguistic heritage, and may encapsulate details about the geographic nature of a named feature, when it was named, and who bestowed it. Moreover, placenames offer insights into the belief and value systems of the name-givers, as well as political and social circumstances at the time of naming,” says Jan.

“In many regions, they also reveal the chronology of exploration and settlement – Australia is an excellent case in point. Between 1606 and 1803, some 900 European placenames were bestowed along the Australian coast. Placenames are not just labels – they are reminders of who we are, and whence we came from,” adds Jan.

“I find the study of placenames very satisfying. It is an area that isn’t written about much or studied to a serious enough extent … I often get asked by radio stations to do segments on placenames, but they are usually after fun stuff, like rude placenames or funny ones. Having said that, however, most people I come across are actually very interested in placenames – what they mean and where they come from,” concludes Jan.

Needless to say, Jan is very pleased with the Christmas Island Early Voyages and its focus on placenames: “I think it is fantastic,” he says.

The Christmas Island Early Voyages stamp issue is available from 15 August 2017, online, at participating Post Offices and via mail order on 1800 331 794, while stocks last.

This article was produced at the time of publication and will not be updated.