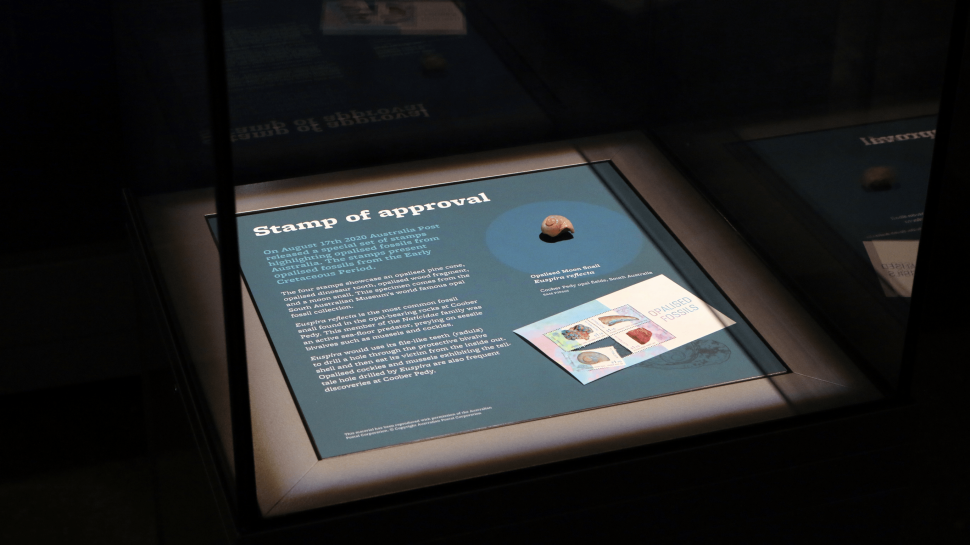

At this major Australian scientific research institution, earth science researchers have not only studied the biodiversity of the Cretaceous Eromanga Sea (a large, shallow body of water that was home to marine molluscs, fish, and swimming reptiles such as plesiosaurs) but are also researching the very the mysterious process of opalisation itself, a conundrum which continues to puzzle scientists.

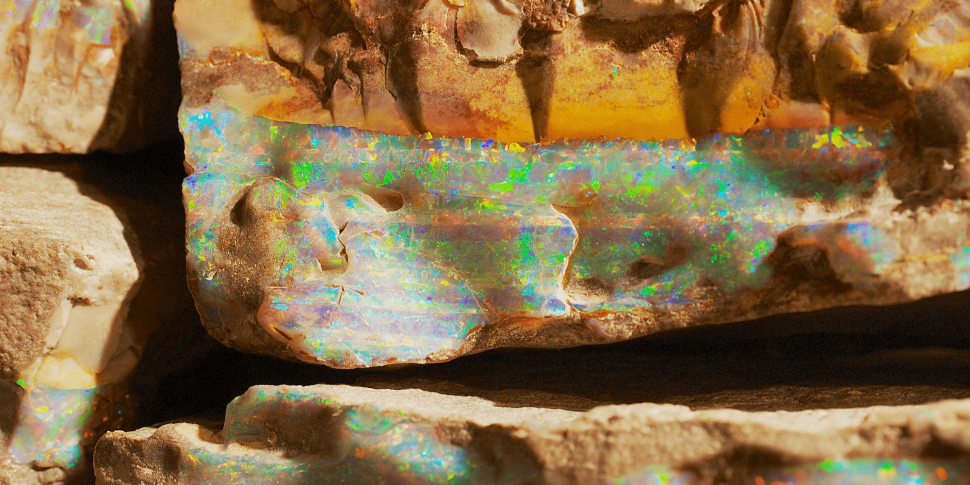

“The best quality opal is often found in fossils. This is because often they have been dissolved by groundwaters, creating a large void which was later filled with opal deposited from super saturated siliceous fluids. There are many theories as to how opal forms, but none so far can account for all occurrences of sedimentary precious opal,” says Ben.

What is it about opalised fossils that makes them both so important and so fascinating?

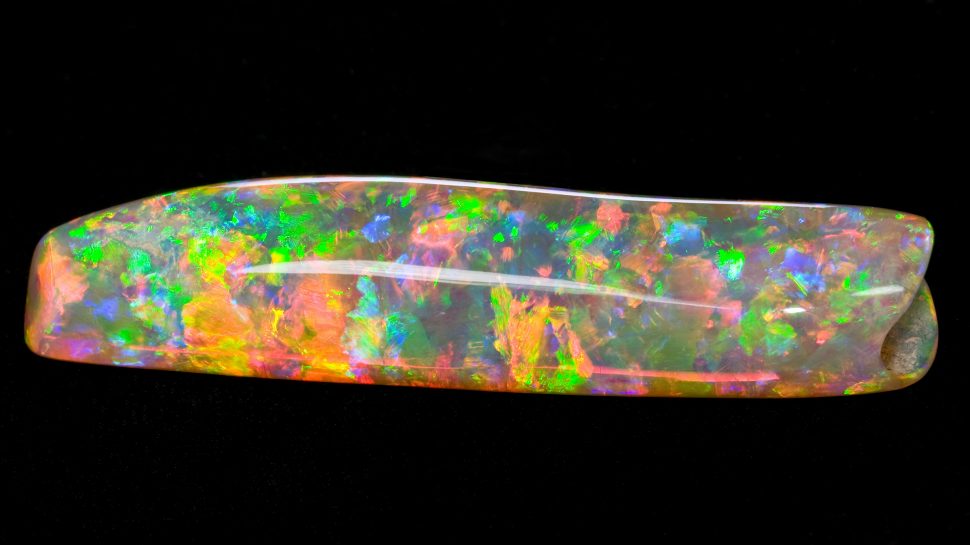

“They combine two super rare natural phenomena – the survival of part of a living thing as a fossil, and the formation of a rare gemstone – in the one object! And they’re beautiful!” exclaims Jenni.

“Australia’s opalised fossils provide rich insights into the history of life on our ancient continent – into how Australia, its geology, landscapes, plants and animals came to be as they are, and how fortunate we are to live in this remarkable place,” adds Jenni.

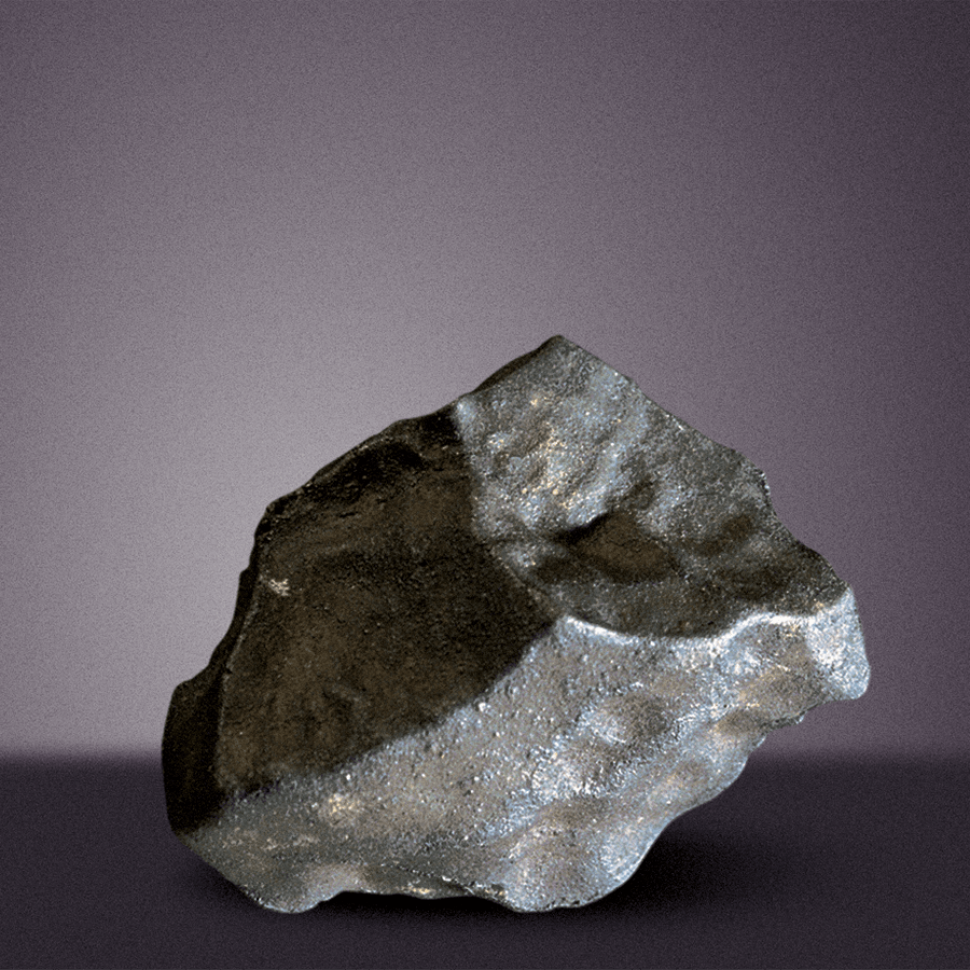

“Australia is one of the only places on Earth where fossils have been preserved in precious opal. The rainbow spectrum of colours makes these fossils more than scientific objects, they become true objects of beauty,” adds Ben.

Most opalised fossils are, perhaps unsurprisingly, discovered by opal miners, though sometimes also by people who fossick for, live near opal fields buy or collect opal.

“The AOC doesn’t have money to buy opalised fossils. Fortunately, some people donate their fossils to the AOC to keep them in Australia, create a legacy for themselves in the collection, make their fossils available for research and share them with the world. Occasionally a generous donor will help us to purchase an important fossil. Sometimes the fossils are donated through the Australian Government’s Cultural Gifts Program. So, the AOC fossil collection is a remarkable collaboration between opal miners, scientists, generous donors and the people of Australia,” says Jenni.