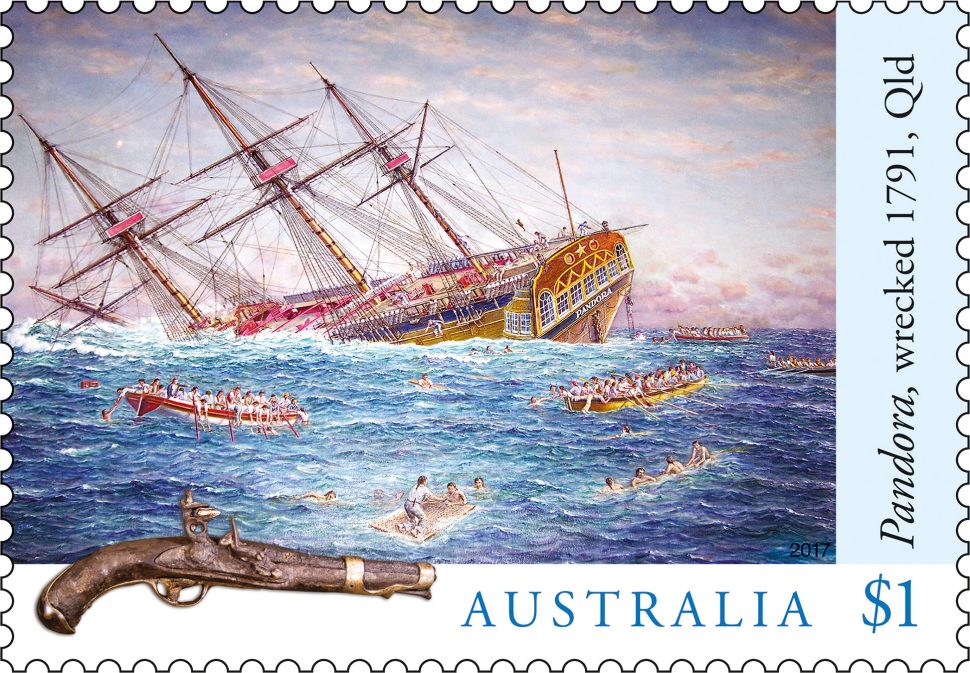

The Shipwrecks stamp issue, which will be released on 29 August 2017, presents three historically and archaeologically significant shipwrecks. The stamps feature paintings by maritime artists of each wreck event, together with a recovered relic, to show the context of each voyage.

In our first instalment of this three part article series, we spoke to artist Adriaan de Jong about the meticulous process involved in researching and painting the Zuytdorp shipwreck. In this article, we move from a Dutch VOC trade ship to a Royal Navy ship sent to hunt down some famous insurgents.

HMS Pandora

HMS Pandora sank on 29 August 1791 on the outer Great Barrier Reef, while returning home from its mission to locate the mutinous Bounty crew in the Pacific Ocean. In total, 35 lives were lost during the wrecking including four of the captured Bounty mutineers.

While 14 of the 25 Bounty mutineers were captured upon Pandora’s arrival in Tahiti, Fletcher Christian, fearing reprisal from the powerful Royal Navy, had fled Tahiti in Bounty with a small band of his supporters – destination unknown. The captured mutineers were shackled in leg irons within a wooden cell, 3.5 metres by 5.5 metres, located on the quarterdeck of Pandora. The prisoners dubbed this “Pandora’s Box”. With the prisoners secure, HMS Pandora searched the Tokelau Islands, Tongan Islands and Fiji for five months, but still could not locate Fletcher Christian and his men. It was then that Captain Edwards decided to head for home.

The wreck of Pandora and its artefacts are looked after by the Cultures and Histories Program at the Queensland Museum Network. Dr Madeline Fowler is the Senior Curator Maritime Archaeology, and her role is to care for the objects to national standards, increase access to the objects and undertake new research on the collection. Alison Mann is the Assistant Collections Manager and is also based at the Museum of Tropical Queensland.

Both Alison and Madeline find the Pandora a fascinating and intriguing story.

“I feel it’s the intertwined stories,” says Alison. “The First Fleet depart England in May 1787, six months later Bounty sets sail. One month after that we have European settlement in Australia, while Bounty is still sailing around the world following orders from the Admiralty. Fourteen months after the British colonise Australia, there is the mutiny on board Bounty and then, after many more months, the Admiralty send Pandora out into a largely uncharted Pacific to hunt down the mutineers. This story is just short of four years in the making!” notes Alison.

For Madeline, the Pandora story starts when the wreck was discovered in 1977 and the subsequent nine seasons of excavation in the 1980s and 1990s.

“The archaeological methods used to record the site differ in some ways to how the site would be documented if it were discovered today. It is interesting to understand how the management of underwater cultural heritage changes over time,” says Madeline.

The museum holds thousands of artefacts from Pandora, including the pistol featured on the stamps and some incredible carved wooden clubs from Polynesia, which the crew would have collected while searching for the mutineers.

I have held that pistol, the one on the stamp, in my hand. It is a tangible connection to this story. All Royal vessels had an armoury, had the weapons to deal with whatever threat came their way. This pistol would have been prepared and ready to fire as Pandora discovered some of the mutineers in the islands of the Pacific. The sailor who held the weapon would have had the orders to shoot if necessary … and our carved wooden clubs from Polynesia?

We have the ship’s log of where and when the islands were visited by Pandora. We can date and locate the clubs to island groups. We see the artistry of the work by the carvers. We can do research today and see how the styles, icons and designs may have changed over 200 years. But also by where the clubs were located in the wreck (in the Officer’s Store, and we know this through the use of archaeological techniques). We believe the clubs were collected by one or more of the officers with the long term view of profiting from the unique circumstances that found them on a voyage in the vast Pacific Ocean.

In the late 1700s, museums back in Britain and Europe would pay good money for these ‘artificial curiosities’ (today, we would call them souvenirs). The Pandora clubs are similar to other significant international collections of Polynesian objects collected during the late 1700s,” says Alison.

“While these artefacts [the pistol and wooden clubs] are significant, they should be interpreted as part of the entire assemblage,” says Madeline. “The pistol is on object within a collection of weapons and accessories that include ordnance, small fire arms, shot for guns and small arms, kegs, gunner’s equipment and bladed weapons. While the war clubs are one example of Polynesian material culture that also includes adze blades, shell blades, poi pounders, lures, hooks, octopus lures, and the modified coconut husks and shell fragments that comprise the Tahitian mourning dress,” adds Madeline.

“Our collection is special because of its diversity and intactness … Pandora wasn’t smashed against a rocky coastline and broken into thousands of pieces. The ship ran onto a reef and had a large hole ripped out of the side. One of the pumps on board whose job it was to pump water out of the hold in a situation like this broke down, the ship took on too much water. There was time to get the long boats off the vessel and get the crew and some prisoners on board. Hence the low loss of life. Then the tide lifted the stricken vessel off the reef but it didn’t get far – it sank in 30 metres of water. Gently, over the next 200 years it was covered in sand. It was this process, this action that gives us the collection we have today,” adds Alison.

To learn more about the HMS Pandora, visit Queensland Museum’s website. To learn more about the entire shipwrecks collection, read Madeline Fowler’s blog article.

In our third and final article, we look at the wrecking of the luxury paddle steamer Clonmel on only her second voyage.

Previous article in this series:

Shipwrecks – capturing our maritime past: Part 1 (Zuytdorp)

The Shipwrecks stamp issue is available from 29 August 2017, online, at participating Post Offices and via mail order on 1800 331 794, while stocks last.

This article was produced at the time of publication and will not be updated.

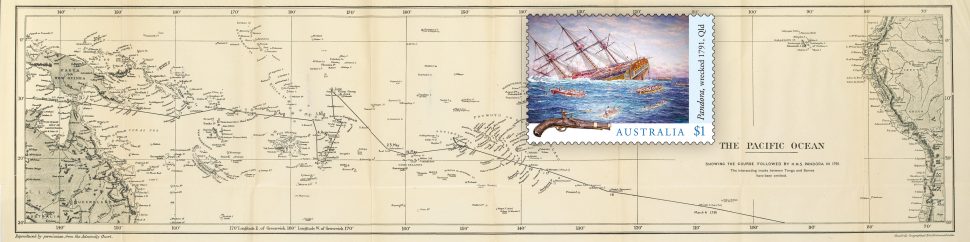

Banner image: Pandora voyage map, State Library Victoria