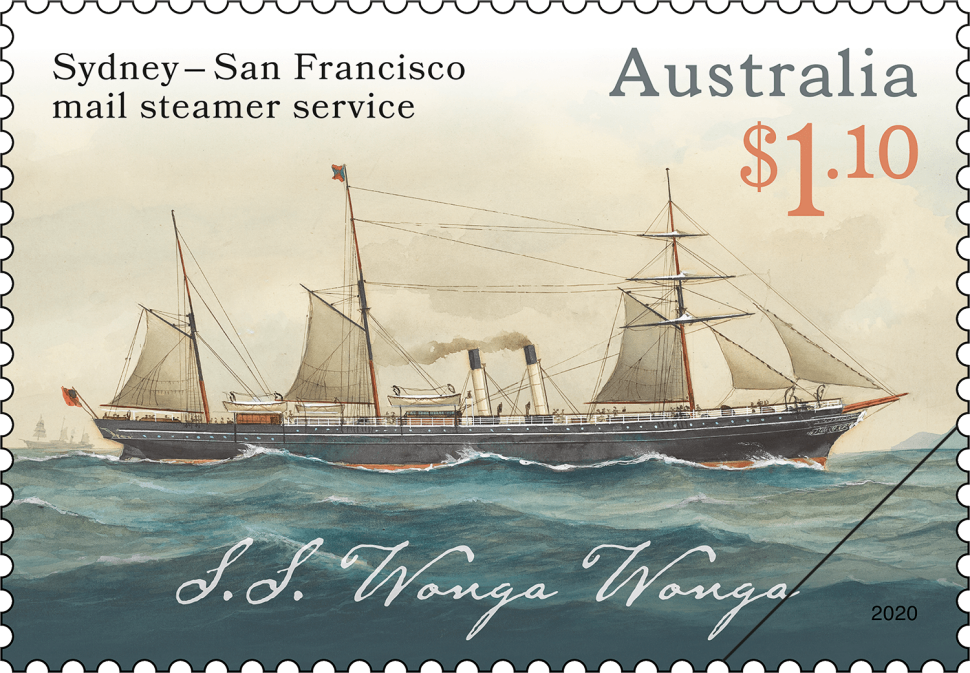

On 3 March 2020, we released a stamp to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the beginning of the Sydney to San Francisco mail steamer service. The visual concept for the stamp design is simple – a watercolour by maritime artist Charles Dickson Gregory of the SS Wonga Wonga, the first ship to carry mail from Sydney to Honolulu, en route to San Francisco.

The philatelic researcher working on the stamp issue located two illustrations by HC Berry captioned “Wonga Wonga” in Douglas Wilkinson’s book, Early New Zealand Steamers (1966). One was of a ship with one funnel, the other a ship with two funnels. While historically linking the Wonga Wonga to Australia, Wilkinson made no mention of Pacific mail service, which seemed unusual, but he did mention a rumoured second ship named Wonga Wonga. Australian maritime history researcher Peter Plowman, who provided expert advice to our researcher on this chapter of the past, confirmed that there were indeed two ships named Wonga Wonga operating in the same era.

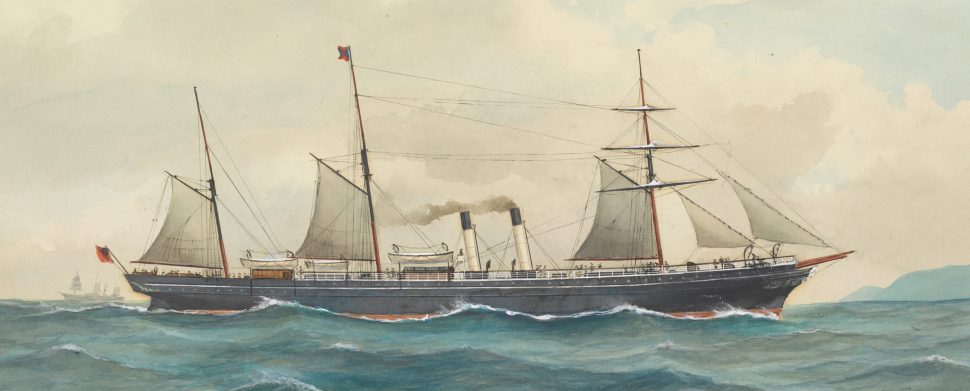

Further books were consulted in the search for visual material for the stamp, including Australian Steamships Past and Present by Dickson Gregory. Illustrated by Gregory himself, this book included a painting of the ship Wonga Wonga that was used on the Pacific mail route. The Pictures Collection catalogue of State Library of Victoria led to the discovery that the original painting by Gregory was in the library’s collection, then titled “unidentified”.

During the stamp issue’s development, a second conundrum emerged. Not only were there two ships of the same vintage and place of construction named Wonga Wonga but also two maritime artists of the period named Charles Dickson Gregory – an intriguing coincidence discovered by Peter Plowman and which led him to unravel the historical threads.

Finding the right Wonga Wonga

“Early Australian shipowners did not adopt a standard format for naming their vessels, and in the case of the Australasian Steam Navigation Company (ASN), the three ships they commissioned in 1854 were named City of Sydney, Telegraph and Wonga Wonga, the latter being the largest vessel they had yet owned,” says Peter.

“What is quite amazing is the fact that at exactly the same time the ASN was having its three ships built in Glasgow, a small Australian firm, Graham, Sands and Company, of Melbourne, was having two ships built in Glasgow by Lawrie & Co, the first to be named Storm Bird, the other to be named Wonga Wonga,” explains Peter.

“The origin for City of Sydney is obvious, and the telegraph was the latest innovation in communications, but from time to time the ASN also used Aboriginal names. In this case, Wonga Wonga was a type of pigeon found along the east coast of Australia, and there was also a Wonga Wonga vine. Just why the ASN would select such an unusual name for its prime ship, however, is unknown,” says Peter.

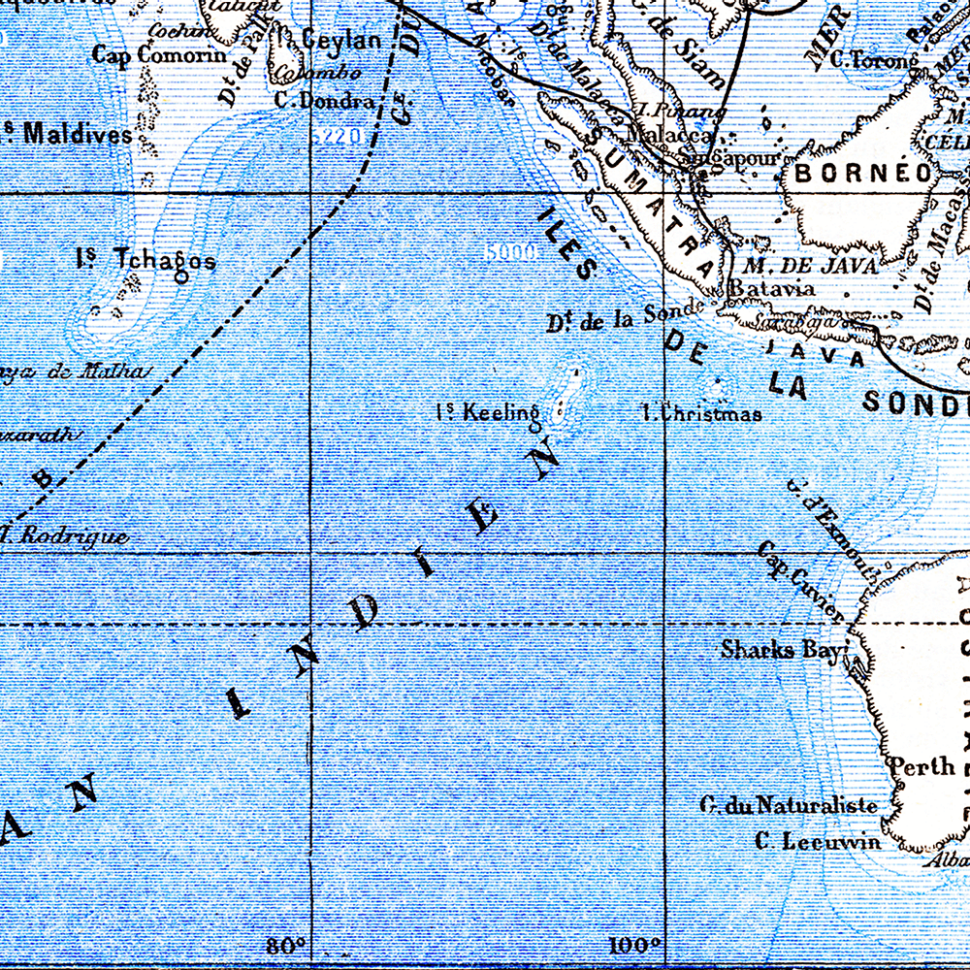

The Graham, Sands and Company vessels were much smaller than the ASN ships, and it seems they were a speculative venture, as Stormbird was offered for sale when it arrived in Melbourne on 13 October 1854, as was the company’s Wonga Wonga, which departed Glasgow on 11 August and reached Melbourne on 17 December. The ASN Wonga Wonga was launched on 15 May 1854 and left Glasgow on 21 September for the delivery voyage to Australia via the Cape of Good Hope, the only stop being two days at St Vincent for coal. This Wonga Wonga arrived in Sydney on 14 December.

“It seems that having two new ships with the same name making their delivery voyages to Australia at the same time from the same departure port caused some confusion for local newspapers, as details of the two ships were mixed up several times in progress reports of their voyages. There was also some confusion with the name, as when the Graham, Sands and Company vessel arrived in Melbourne it was initially reported in the newspapers as being named Wanga Wanga,” notes Peter.

In size and general appearance, the two vessels were quite different. The Graham, Sands and Company Wonga Wonga was 108 gross tons, 107 feet long, had one funnel and two masts, and had accommodation for 12 cabin and 20 steerage passengers. It was sold to New Zealand owners in 1855 and went on to have a very successful career in that country, until being wrecked on 2 May 1866 off Greymouth. This was the vessel depicted in the painting by HC Berry.

The ASN Wonga Wonga was 662 gross tons, 207.2 feet long with a beam of 25.3 feet, had one funnel and three masts, and accommodation for 54 saloon, 50 intermediate and 120 steerage passengers. This vessel enjoyed more than a decade of successful operation on the Australian coastal trades as a single-funnel steamer. However, in 1868 it was refurbished; it was cut in two and lengthened by 37 feet, had extra accommodation fitted, and new boilers and a second funnel were added. This was the appearance of the ship in the painting by Charles Dickson Gregory.

In 1870, this Wonga Wonga was chartered from the ASN by HH (Hayden Hezekiah) Hall, to carry mail and passengers from Sydney to Hawaii, from where they were transported to San Francisco on US ships. Hall had secured the initial contract for the mail service with the New Zealand government, with the New South Wales colonial government agreeing to provide a subsidy for the service for 12 months.

Who was Charles Dickson Gregory?

Peter Plowman had been familiar with the name Charles Dickson Gregory for many years, but did not know very much about him, other than the fact that he had written two books that featured many of his own paintings.

When Peter began to research the man and his artistic works, including the painting of the SS Wonga Wonga featured on the stamp, he soon discovered there had been two maritime artists in Australia named Charles Dickson Gregory, one with birth and death years listed as 1850–1920, the other 1871–1947.

The question then became: were these two men related?

“There is not much biographical information available about the elder Charles Dickson Gregory (b. 1850), though he is listed briefly in several reference books about Australian artists, including The Encyclopaedia of Australian Artists, compiled by Alan McCulloch, and Dictionary of Australian Artists, edited by Joan Kerr. They both state that he was born in London but was brought to Australia in 1851 as an infant and spent the next 22 years in the country. He tried to make a living on the gold fields, but when that failed, he was able to make a living by painting portraits of ships and various other subjects, eventually opening his own studio in South Melbourne. He went back to Britain in 1873 to study at the Royal Academy Schools, and it seems he never returned to Australia, which means it’s hard to determine any familial connection with the younger Charles Dickson Gregory, who was born in Australia in 1871,” says Peter.

“I was able to immediately discount the first of these gentlemen as being the artist of the painting featured on the stamp, as the two books in my collection had been published in 1929 and 1935 and included material on ships and events after 1920. The existence of an elder Charles Dickson Gregory might explain why the younger Charles Dickson Gregory signed his paintings and authored his books as Dickson Gregory, and it seems he was known to friends as Dickson rather than Charles,” says Peter.

Dickson Gregory was a ship enthusiast who painted as a hobby, and, it seems, only came to prominence in Australia following the publication of his first book in 1929, Australian Steamships Past and Present. Despite the Australian theme and the quality of the content, apparently no Australian publisher had any interest in it, so it was printed in Edinburgh and published in Britain by The Richards Press Ltd of London.

It is said that King George V and the Prince of Wales each accepted a copy of the publication. The King showed particular interest in Gregory’s painting of the RMS Ophir, featuring on the frontispiece, as he and Queen Mary, then Duke and Duchess of York, had made their historic trip to Australia on the vessel in 1901 for the opening of Australia’s first federal parliament.

Dickson Gregory was involved in the formation of the Shiplovers’ Society of Victoria in 1930, and he was often asked to give talks. In one newspaper interview, Gregory stated his father, George, was the chief engineer on the Chusan when it first came to Australia. “Chusan has a very important place in the maritime history of Australia, as it was the first vessel owned by the P & O Line to come to this country, in 1852.” says Peter.

George Gregory later settled in Australia, and Dickson said he first went to sea with him at around six years of age, but he never spent any time as a seaman, preferring to be a passenger.

‟It is interesting that McCulloch only refers to the elder Charles Dickson Gregory as Charles Gregory, and it seems that he signed his paintings completed in England this way. Before leaving Australia, Gregory appears to have developed a sizeable reputation as an artist, and, despite his tender years, was listed as a founding member of the Victorian Academy of Fine Arts in 1870. The Encyclopaedia of Australian Artists states, ‘He produced a large volume of work while in Australia including watercolours of marine subjects and painted birds.’”

The Dictionary of Australian Artists states, ‘Gregory’s youthful Australian years were also artistically productive. He painted numerous watercolours of ships, including Sailing Ship Preussen, SS Katoomba, City of Hobart, Sophia Jane and Wreck of the Admella, but, notes Peter, this is inaccurate.

“The painting of Sophia Jane is definitely by the younger Charles Dickson Gregory (Dickson Gregory), being one of the colour plates included in his book printed in 1929. Also, the Katoomba was not built until 1878, five years after the elder Gregory left Australia, and that painting is also in Gregory’s 1929 book, though in black and white, as is the painting of the City of Hobart. The painting titled Wreck of the Admella is also clearly signed by Dickson Gregory, and he did a number of other wreck paintings. The Preussen was a five-masted sailing ship built in 1902 and wrecked in 1910, which never came to Australia, and that painting was probably done by the elder Charles Dickson Gregory when he lived in England. All of this leaves a question mark over the authenticity of any maritime paintings claimed as being created by the elder Charles Dickson Gregory in Australia,” says Peter.

Surprisingly, there is no entry at all for the younger Charles Dickson Gregory in the Dictionary of Australian Artists, and in The Encyclopaedia of Australian Artists McCulloch is rather dismissive of his work, the entry merely stating:

GREGORY, CHARLES DICKSON (Active from c 1890, Melb). Painter, jeweller. He worked for the firm of Alfred Felton and was known for marine paintings, which, although similar in style, lack the finish of G F Gregory. The two were not related.

This attitude may be in part due to the misattribution of some of his paintings to the elder Charles Dickson Gregory. Interestingly, though, the elder Charles Dickson Gregory is not mentioned in this entry, which points to there being no known familial relationship, particularly as the entry goes to lengths to distance the younger Gregory’s work from another maritime artist, GF Gregory. In fact, there was both a father and a son with the name George Frederick Gregory who were maritime painters in Australia at this time, as was another son, Arthur Victor Gregory (1867–1957).

“Among the maritime paintings I had seen in various books over the years were some signed AV Gregory, and I had thought that AV Gregory was probably the brother of the younger Charles Dickson Gregory. This seemed to be a logical conclusion considering their years of birth (1867 and 1871 respectively), and the fact that both had a father named George,” says Peter.

However, not only does The Encyclopedia of Australian Artists dismiss this, none of the entries about the George Frederick Gregory family of maritime artists make any mention of either man named Charles Dickson Gregory. In addition, an obituary for Dickson Gregory indicates the presence of a sister, but no brothers.

“It seems, therefore, that the men named Charles Dickson Gregory were not related to any other artists with the surname Gregory from this period, and most likely not related to each other. It’s all just a very interesting coincidence,” says Peter.

“Dickson Gregory is held in high regard in maritime art circles in Australia, in contrast to The Encyclopedia of Australian Artists’ summary of his career, which was no doubt in part due to the misattribution of his work,” says Peter.

Dickson Gregory’s painting of the ASN’s Wonga Wonga, after it was lengthened in 1868, is reproduced on the $1.10 Sydney to San Francisco mail steamer stamp. The State Library of Victoria has since updated its description of the original painting in its collection, attributing it to Dickson Gregory.

The journey to verify both ship and artist was certainly an interesting one for Peter, who said, “being an avid researcher of Australian maritime history, it is always particularly pleasing to be asked to partake in something quite different from my usual projects”.

The Sydney–San Francisco Mail Steamer Service: 150 Years stamp issue is available, online, at participating Post Offices and via mail order on 1800 331 794, while stocks last.

View the gallery and technical details from this issue.

This content was produced at the time of the stamp issue release date and will not be updated.