Heather’s current roles include Honorary Associate Professor at Macquarie University; Science and Technology of Australia Superstar of STEM; and Governing Councillor of the Geological Society of Australia. Heather is also the Co-Founder and President of the Women in Earth and Environmental Science Australasia (WOMESSA). WOMEESA aims to create a unified network of women working in geoscience within academic, government and industry, to raise the visibility of women and provide role models.

“More than one billion people in the world are estimated to live within the range of direct impact of volcanic eruptions. Understanding more about how volcanoes work, for example, what triggers volcanic eruptions, how fast magma moves from its source to the surface, helps to reduce risk from volcanic hazards,” notes Heather.

An exciting research project Heather is currently working on is taking a microscopic look at Australia’s volcanoes.

“In the same way that tree rings can tell you about what the rainfall and temperature was like when a tree grew, the crystals within volcanic rocks hold clues to their journey through the Earth. I use x-rays and electron beams to uncover the secret histories of volcanic crystals, many of which are smaller than the thickness of a human hair,” says Heather.

“Through studying the spectacular shapes of volcanic crystals and their chemical patterns I will estimate the time it took for molten rock (magma) to travel from deep in the Earth’s mantle, from at least 30 to 40 kilometres beneath our feet, to the surface at some of Australia’s most recently active volcanoes. This will provide an estimate of the minimum eruption warning time of past eruptions. Preliminary results indicate that in at least at some volcanoes in southeast Australia it only took around two to three days for magma to reach the surface all the way from the upper mantle… that’s fast!” adds Heather.

There are ways for the general public to get more involved in the world of volcanoes too. As part of her research, Heather is surveying the general public on their opinion of volcanic hazards. In addition, the New South Wales government has recently launched a new “geotrail” around Warrumbungle volcano in New South Wales.

“There are self-drive and walking trail options and it’s a great way to get outdoors and learn more about Australia’s fiery past,” says Heather.

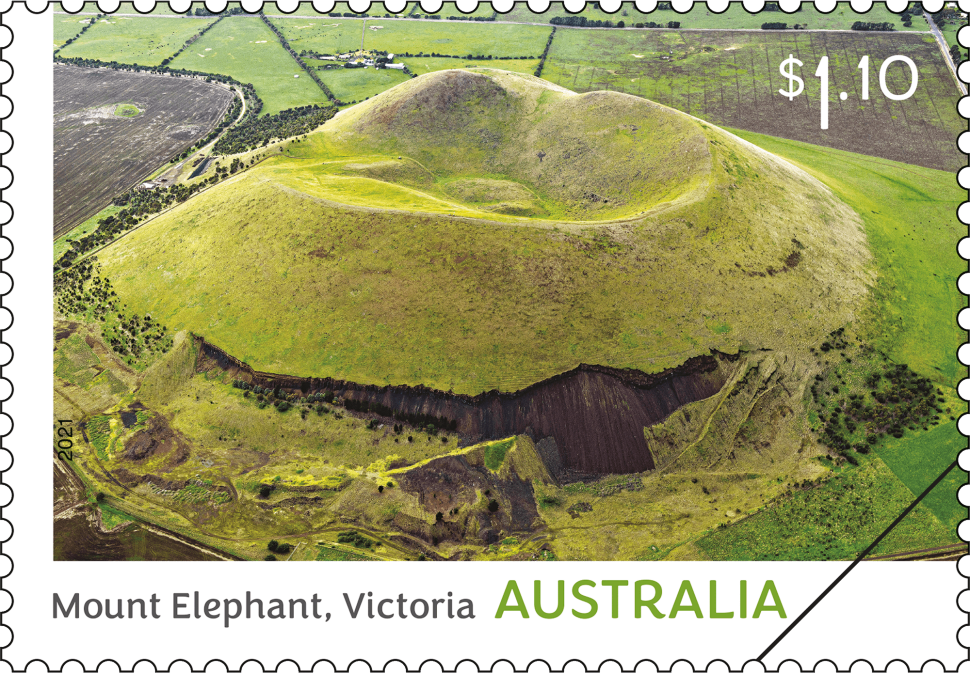

Heather is also very pleased to see volcanoes reach the public as a theme on Australian stamps:

“When you think of Australia, images of koalas and kangaroos, sun-drenched beaches and vast red landscapes probably come to your mind, but probably not volcanoes. Yet, there’s a vast tract, more than 4,000 kilometres in length, down the east coast of Australia that has been forged by volcanic fire more than tens of millions of years ago to just 5,000 years ago. I think it’s absolutely wonderful that Australia Post is raising awareness of Australia’s rich volcanic heritage and I hope that it will encourage people to find out more and hopefully visit a volcano.”