In 1788, Lieutenant Philip Gidley King, along with a party of 15 convicts and seven free men, arrived on Norfolk Island to set up a British colony. It ceased in 1814, in part due to rising costs and the impracticalities of its distance from New South Wales. Both convicts and free settlers farmed small holdings of land, and by 1804 free settlers heavily outnumbered convicts.

The island lay abandoned until the establishment of a second penal settlement in June 1825, when Captain Turton arrived with a party of 50 soldiers, 57 convict, six women and six children. The intention was to make this settlement a much harsher place for convicts than its predecessor, and in this sense the colony succeeded. It closed in 1855, and the following year saw the arrival of the descendants of the infamous Bounty mutineers, who had outgrown Pitcairn Island.

As a result of this convict past, Norfolk Island boasts a large collection of penal settlement buildings, ruins and archeological remains. These sites make up the Kingston and Arthurs Vale Historic Area (KAVHA), which sits on the southern side of Norfolk Island, on the Kingston coastal plain. KAVHA is part of the Australian Convict Sites World Heritage Property, which comprises 11 sites that tell important and evocative stories about convict life. KAVHA is also listed on the National Heritage list and the Norfolk Island Heritage Register.

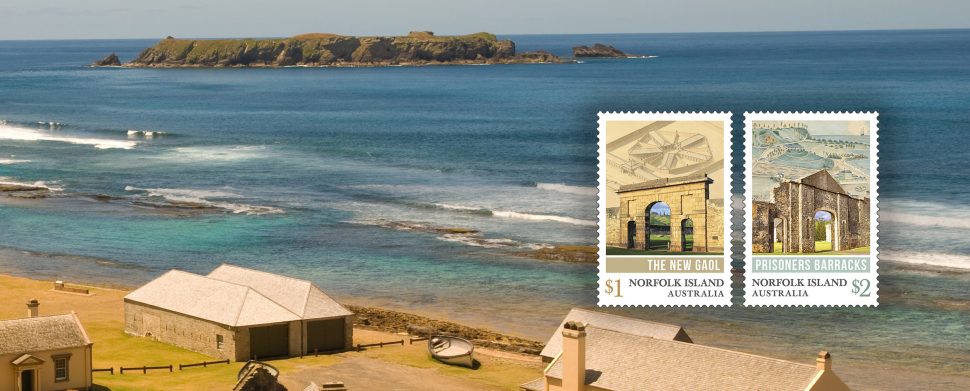

The Norfolk Island Convict Heritage stamp issue, which will be released on 19 September 2017, presents two important KAVHA sites from the second penal colony: the New Gaol, completed in 1847 to house recalcitrant convicts and a rare example of pentagonal design; and the Prisoners Barracks, completed in 1835 to house close to 1,000 men and boys in cramped conditions. The stamps combine modern photographs of each site with evocative historical imagery. . Learn more about the stamps and imagery.

Sites of national and international significance

KAVHA is recognised for being one of the best surviving examples of large-scale convict penal transportation and colonisation in the world, but it is also significant as the only site in Australia with evidence of early Polynesian settlement (pre-1788). Stone tools have been found within KAVHA and archaeological investigations in the Emily Bay area have revealed evidence of East Polynesian culture, dating Polynesian presence on the island to between AD 1200 and AD 1600. And, as mentioned above, KAVHA is the arrival place of the Pitcairn Islanders, who were given permission by the British to settle on Norfolk Island in 1856 and included descendants of the infamous Bounty mutineers.

Some of the most significant buildings at KAVHA include Government House (built in 1829), which is one of the earliest and most intact remaining government house buildings in Australia, and the Commissariat Store, dating from 1835, which is the considered the finest remaining military commissariat store in Australia from the colonial era (pre-1850). Quality Row (originally named Military Row) was first laid out in 1825 and is one of the most extensive remaining colonial penal settlement streets in Australasia. It contains elegant houses that provided accommodation for military and civil officers, some of which are still in use today (one as the Norfolk Island Golf Course clubhouse and another as the Norfolk Island Museum and Research Centre). The site also includes the remains of the only known human-powered crank mill built in Australia before 1850, and two of the earliest remaining large-scale engineering works in Australia: a landing pier and a sea wall.

While the buildings and ruins visible today generally date from the second penal settlement period, some were constructed from the foundations of earlier colonial settlement buildings. While the sites sit within a picturesque coastal setting, encircled by green rolling hills, the reality of life as a convict on Norfolk Island was grim, particularly during the notoriously harsh second settlement.

A brutal life

Convict life was brutal. Convicts in the second penal settlement worked in gangs on building or agricultural work, over long days. Agricultural work was conducted manually with hoes and spades, without the aid of machinery or working animals. As well as the cramped accommodation within the Prisoners Barracks (up to 120 people within a single ward), food was scarce and of poor quality, leading to many deaths. Convicts who broke the rules were sent to the New Gaol and given more strenuous work tasks; some even having their sentences extended. Floggings were common, even for small misdemeanours. However, the convict population was already considered the ‘worst of the worst’ and the most hardened men seemed undeterred by the unrelenting nature of the punishment. Some even dared to stage uprisings against the regime, despite the very real risk of flogging or even death.

And the convict system on Norfolk certainly bred callous leaders, particularly Captain James Morisset who was commandant between 1829 and 1834.

Attempts at reform

Between 1840 and 1844, there was some attempt to reform the penal system and humanise the treatment of convicts. Commandant Alexander Maconochie introduced a merit-based system that many of us would recognise in the present day: the ability to reduce your sentence (and even reform yourself) if you obey the rules and work hard. While many historical accounts have branded this system a failure (there was an attempted seizure of a ship by convicts and a revolt), there is also much evidence that it not only improved conditions for prisoners but also lead to a relatively peaceful phrase in the colony’s history. A high percentage of convicts who left the island did not re-offend. However, Maconochie’s efforts were not appreciated by his superiors, as evidenced by their choice of replacement, Major Joseph Childs who, like Morriset, favoured a relentlessly strict and cruel regime.

The end of the convict era

The severity of the Norfolk Island convict system continued, until a visit by Bishop Robert Wilson helped to bring an end to the penal system on the island. His post-visit report detailed the appalling conditions and the settlement gradually closed over eight years, though a small contingent remained on Norfolk to continue work on the land and hand it over to the Pitcairn Islanders, who arrived on 8 June 1856.

View the gallery of stamps and technical details for this issue.

The Norfolk Island Convict Heritage stamp issue is available from 19 September 2017, online, at participating Post Offices and via mail order on 1800 331 794, while stocks last.

This article was produced at the time of publication and will not be updated.